Battles and Bombardments

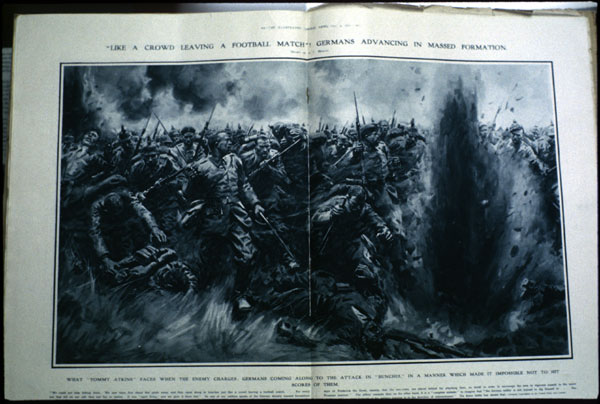

From The Illustrated London News of October 3, 1914: the Germans were also not immune to trying massed frontal assaults. But it didn't take long until they became the masters of the defense in depth (a talent to which the accompanying text alludes).

From The Illustrated London News of October 3, 1914: the Germans were also not immune to trying massed frontal assaults. But it didn't take long until they became the masters of the defense in depth (a talent to which the accompanying text alludes).

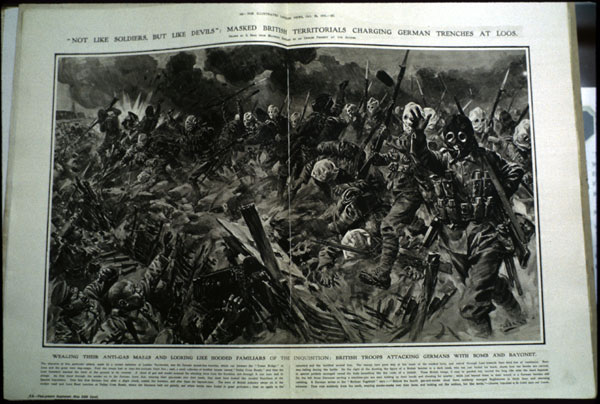

From The Illustrated London News of October 30, 1915: a surreal depiction of the Battle of Loos, September-October, 1915. Earlier in the year, the Germans had initiated chemical warfare by discharging chlorine gas at the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22nd. Such a fiendish weapon was seen as typically "unsportsmanlike" of the Huns, but half a year later at Loos, the British were no longer above employing it themselves.

From The Illustrated London News of October 30, 1915: a surreal depiction of the Battle of Loos, September-October, 1915. Earlier in the year, the Germans had initiated chemical warfare by discharging chlorine gas at the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22nd. Such a fiendish weapon was seen as typically "unsportsmanlike" of the Huns, but half a year later at Loos, the British were no longer above employing it themselves.

This artistic rendering is misleading (click here to read the text accompanying the illustration): the Battle of Loos was a slaughter of British troops — a foreshadowing of the Somme a year later — where the combination of machine guns in defensive positions, fronted by barbed wire proved devastating to infantry. German machine gunners surfeited and sickened by the slaughter stopped firing. Great War poet and memorist Robert Graves recalled the Battle of Loos in Goodbye to All That — especially the fiasco involved in discharging the "accessory" (the secret name for the chlorine gas), most of which blew back into the British trenches. Graves remarked that the only significant result of the Battle of Loos was that it cost the life of one of the three greatest poets to be killed in the war, Charles Sorley (Graves considered Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg the other two). The disaster at Loos precipitated the removal of General Sir John French, commander of the BEF. In December 1915, he was replaced by General Sir Douglas Haig who immediately began plans for an offensive on the Somme to be carried out that next summer.

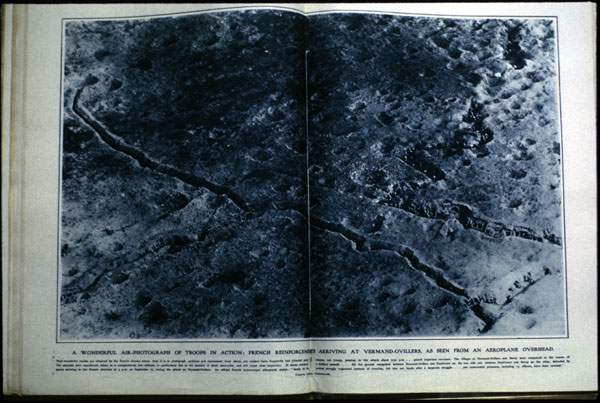

From The Illustrated London News of October 14, 1916, a photograph of trenches in the French sector on the Somme (click here to read the accompanying text). The Battle of the Somme has come to occupy an especially important place in the British imagination -- akin to the image Verdun holds for Frenchmen: the loss of innocence, futility, and waste. The Great War at its worst. (For more on the Somme, see David Jones' epic prose-poem In Parenthesis. See also "Gentlemen, when the barrage lifts", the account from Paul Fussell's The Great War and Modern Memory.)

From The Illustrated London News of October 14, 1916, a photograph of trenches in the French sector on the Somme (click here to read the accompanying text). The Battle of the Somme has come to occupy an especially important place in the British imagination -- akin to the image Verdun holds for Frenchmen: the loss of innocence, futility, and waste. The Great War at its worst. (For more on the Somme, see David Jones' epic prose-poem In Parenthesis. See also "Gentlemen, when the barrage lifts", the account from Paul Fussell's The Great War and Modern Memory.)

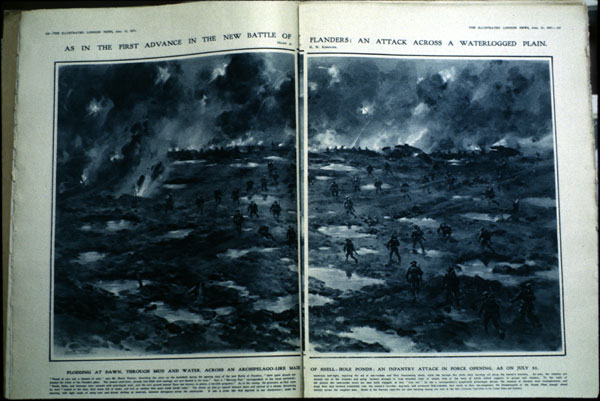

From The Illustrated London News of August 11, 1917: artist's version of July 31, 1917 — the first day of the Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele (click here to read the illustration's accompanying text).

From The Illustrated London News of August 11, 1917: artist's version of July 31, 1917 — the first day of the Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele (click here to read the illustration's accompanying text).

A year after the slaughter on the Somme [above] in Picardy, General Sir Douglas Haig attacked out of the Ypres salient in Flanders. Whereas at the Somme the bombardment had consisted of 1,537 guns firing for seven days for a total of 1,627,824 rounds, now Haig's preparatory bombardment lasted for 14 days, with 3,000 guns firing 4,283,550 shells. The terrain in Flanders is naturally waterlogged, and the preparatory bombardment churned up the ground, destroyed dikes and ditches until — helped by the heaviest rains in decades — No-Man's Land was turned into a sea of mud. Haig incorporated the newfangled landships, "tanks" — but not in sufficient numbers, and across terrain that wouldn't support them. The Battle of Third Ypres lasted for three month, until November. The British gained 5 miles at a cost of a quarter million casualties. 42,000 men simply disappeared, swallowed up in the glutinous mud of Passchendaele. (To learn what happened to the battlefields after the war, including the clean-up of unexploded ordnance, click here.)

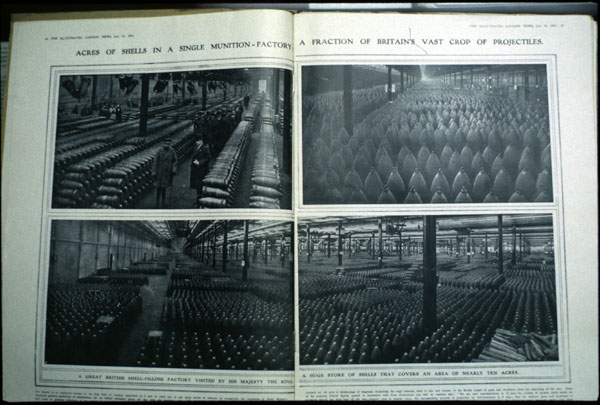

A photograph from The Illustrated London News, January 27, 1917, showing King George V (1865-1936) touring a munitions plant — probably the Chilwell Factory near Nottingham (click here to read the photo's accompanying text). Most of the projectiles appear to be 8" (near the King), and 12"-15" howitzer shells (in the upper right-hand photo) — the latter weighing somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 lbs. each. (To learn about the clean-up of unexploded ordnance after the war, click here.)

A photograph from The Illustrated London News, January 27, 1917, showing King George V (1865-1936) touring a munitions plant — probably the Chilwell Factory near Nottingham (click here to read the photo's accompanying text). Most of the projectiles appear to be 8" (near the King), and 12"-15" howitzer shells (in the upper right-hand photo) — the latter weighing somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 lbs. each. (To learn about the clean-up of unexploded ordnance after the war, click here.)

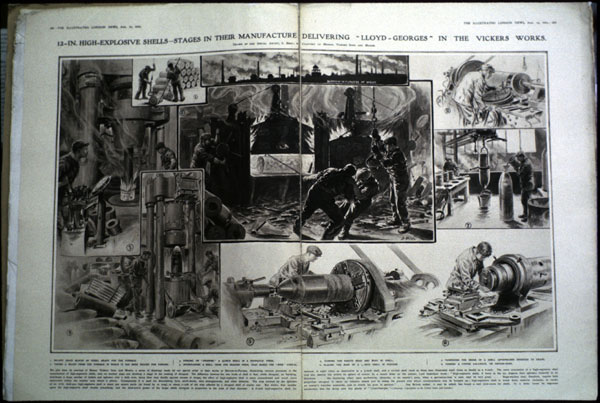

From The Illustrated London News of August 14, 1915: a collage showing the lengthy, precise manufacturing process involved in producing artillery shells — in this case, 12" shells (click here to read the accompanying text that explains each step in the process). The human cost aside for a moment, what a tragic, senseless waste of resources, energy, and labor when one contemplates the amount of ammunition used in the multi-million-round preparatory bombardments before such battles as the Somme and Passchendaele. (To learn about the clean-up of unexploded ordnance after the war, click here.)

From The Illustrated London News of August 14, 1915: a collage showing the lengthy, precise manufacturing process involved in producing artillery shells — in this case, 12" shells (click here to read the accompanying text that explains each step in the process). The human cost aside for a moment, what a tragic, senseless waste of resources, energy, and labor when one contemplates the amount of ammunition used in the multi-million-round preparatory bombardments before such battles as the Somme and Passchendaele. (To learn about the clean-up of unexploded ordnance after the war, click here.)