Children's Literature

In Flanders Fields : the Story of the Poem by John McCrae, / by Linda Granfield, illustrated by Janet Wilson. -- <Toronto> : Stoddart, 1996.

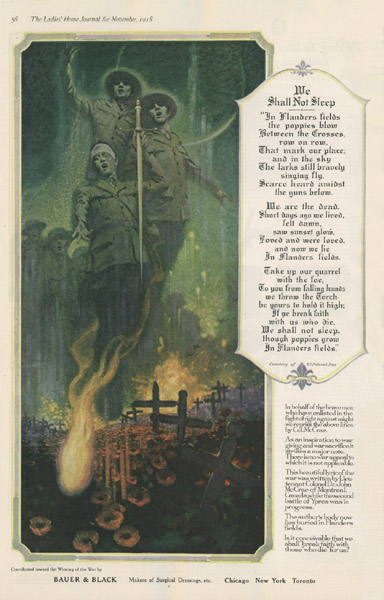

John McCrae's poem "In Flanders Fields" is probably the most well-known poem of the Great War. Written in early May 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, it was an instant hit after appearing in the December 8th issue of Punch. The poem arrived with the same timeliness as Rupert Brooke's sonnets ("I. Peace," and "V. The Soldier") had done a year earlier. It struck a ready nerve in many readers, and was "answered" - politely parodied - by would-be poets on both sides of the Atlantic. LTC John McCrae (b. November 30th, 1872), a Canadian doctor from a military family, continued to serve until overworked and demoralized, he died of pneumonia on the 28th of January, 1918, at age 45. "In Flanders Fields" draws upon the same image of passing-the-torch as Henry Newbolt's "Vitai Lampada" ("They Pass On the Torch of Life"). McCrae's use of the floppy, scarlet poppy as a symbol of love, death and sleep was not new, and in Great War poetry not limited to his poem only. What is considered by most critics the best poem of the war, Isaac Rosenberg's "Break of Day in the Trenches," also incorporates the poppy. But it was McCrae's "In Flanders Fields" that forever associated the poppy with the dead of the Great War. (For an intriguing catalog of the many Western Front motifs combined in "In Flanders Fields" - the image of sky seen through the overhead opening of a trench, singing larks, soldiers as lovers, etc. - see Paul Fussell's The Great War and Modern Memory.)

War Game / Michael Foreman. -- 1st U.S. ed. -- New York : Arcade : Distributed by Little, Brown and Co., 1994.

Michael Foreman's War Game is based on the stories of the spontaneous Christmas truce of 1914 on the Western Front. Four boys from the same soccer team join up together in the heat of the patriotic excitement of August 1914, and go in the same unit to the Western Front. They participate in a spontaneous Christmas truce with the Germans opposite them across No-Man's Land, even striking up a friendly soccer game. After the impromptu truce, the war resumes, fresh Prussians replace the friendlier Saxon Germans across No-Man's Land, and in a hopeless counterattack, all four boys are killed. (Incidentally, Foreman dedicates the book to four uncles who died in the war.) War Game skillfully combines a number of literary motifs from the Great War motifs into one tale -- in the same manner as McCrae's "In Flanders Field" combines a number of motifs into one poem: the idea of the "game" in Sir Henry Newbolt's "Vitai Lampada" ("They Pass On the Torch of Life"); the preaching vicar (Dean Inge of St. Paul's reciting Rupert Brooke's sonnet "V. The Soldier" on Easter Sunday, 1915); and the satisfied squire in his pew in Siegfried Sassoon's "Memorial Tablet (Great War"). War Games also combines several of the most intriguing bits of Western Front lore: the spontaneous Christmas truce of 1914 (which did happen -- click here for an Illustrated London News account from the time), its soccer game played between members of the opposing armies (purely anecdotal, but for the empty "Bully Beef" tin that might've been kicked around a bit), and kicking a soccer ball into No-Man's Land before "going over the top" (which was done more than once, but only once by a certain Captain Nevill at the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916 -- click here for Paul Fussell's account in The Great War and Modern Memory).

Also, implicit in the story of War Game is the tragedy of the many "Pal's Battalions" who enlisted in units formed up from members of the same villages, towns and neighborhoods. These same villages, towns and neighborhoods were then devastated when their young men were slaughtered together in the major battles on the Western Front -- as were the Irish of Ulster who suffered horrendous losses in the Battle of the Somme (See also Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Toward the Somme). Similar tragedies happened to regional units in the American Civil War, and to National Guard units in World War I and II. (For more on Michael Foreman's War Game, click here to see a further book review.)