Fiction & Drama

" . . . abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates." Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)

Under Fire; the Story of a Squad, by Henri Barbusse; tr. by Fitzwater Wray. -- New York. E. P. Dutton & co. <1917>

Henri Barbusse (1874-1935) was a French soldier. Under Fire is the English translation of his acclaimed anti-war novel Le Feu (1916) -- one of the first "serious" (that is critical, thoughtful, truthful) works about the war, and one that influenced many other writers and even, later, film makers. It may not be too much to say that, along with The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900, it "presides over the Great War in a way that has never been sufficiently appreciated" (Fussell, 159). Siegfried Sassoon read Le Feu in French, was profoundly effected by it, and included a long quotation, in French, at the beginning of Counter-Attack. At Craiglockhart, Sassoon loaned his French copy of Le Feu to Wilfred Owen, was in turn "set alight" by it. (The Lee Library also holds a copy of Le Feu translated into German: Das Feuer (Tagebuch einer Korporalschaft). -- Zurich, M. Rascher, 1918.)

Henri Barbusse (1874-1935) was a French soldier. Under Fire is the English translation of his acclaimed anti-war novel Le Feu (1916) -- one of the first "serious" (that is critical, thoughtful, truthful) works about the war, and one that influenced many other writers and even, later, film makers. It may not be too much to say that, along with The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900, it "presides over the Great War in a way that has never been sufficiently appreciated" (Fussell, 159). Siegfried Sassoon read Le Feu in French, was profoundly effected by it, and included a long quotation, in French, at the beginning of Counter-Attack. At Craiglockhart, Sassoon loaned his French copy of Le Feu to Wilfred Owen, was in turn "set alight" by it. (The Lee Library also holds a copy of Le Feu translated into German: Das Feuer (Tagebuch einer Korporalschaft). -- Zurich, M. Rascher, 1918.)

All Quiet on The Western Front / Erich Maria Remarque ; translated from the German by A. W. Wheen. -- Boston : Little, Brown, & Company, 1929.

Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) was a German soldier in the Great War (although there is still some controversy as to just how much combat he experienced -- and further controversy as to just how much difference that makes in his fiction). All Quiet on the Western Front is the English translation of Remarke's Im Westen nichts Neues -- one of the German classics of the war, and a book that Hitler (himself a gassed and decorated Corporal in the Great War) hated, would like to have banned, and burned when he came to power, for (among other things) what he and the Nazi's saw as its portrayal of defeatism and weakness in the German Army during the war.

Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) was a German soldier in the Great War (although there is still some controversy as to just how much combat he experienced -- and further controversy as to just how much difference that makes in his fiction). All Quiet on the Western Front is the English translation of Remarke's Im Westen nichts Neues -- one of the German classics of the war, and a book that Hitler (himself a gassed and decorated Corporal in the Great War) hated, would like to have banned, and burned when he came to power, for (among other things) what he and the Nazi's saw as its portrayal of defeatism and weakness in the German Army during the war.

The Spanish Farm Trilogy, 1914-1918 / by R.H. Mottram. -- London : Chatto & Windus, 1927.

The Spanish Farm Trilogy, 1914-1918. -- London : Chatto & Windus, 1927, by R.H. (Ralph Hale) Mottram (1883-1971), revolves around the Vanderlynden ("Spanish") farm in Flanders. Mottram followed the trilogy with Ten Years Ago : Armistice & Other Memories, Forming a Pendant to 'The Spanish Farm Trilogy' / by R. H. Mottram ; with a foreword by W. E. Bates, late C.Q.M.S., H.A.C. -- London : Chatto and Windus, 1928.

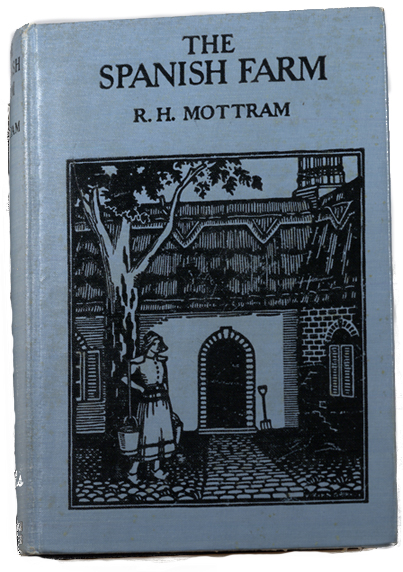

The Spanish Farm / by R. H. Mottram ; with a preface by John Galsworthy. -- London : Chatto & Windus, 1924.

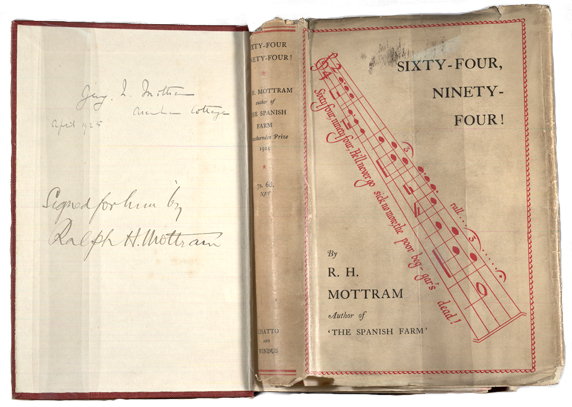

Sixty-four, ninety-four! / by Ralph Hale Mottram, author of The Spanish Farm. -- London : Chatto and Windus, 1925.

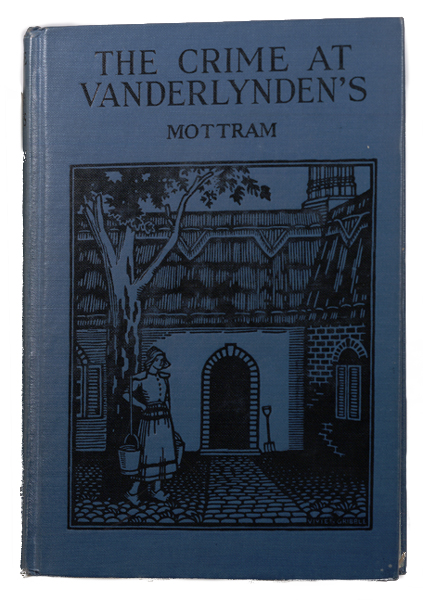

The Crime at Vanderlynden's / by R. H. Mottram, author of The Spanish Farm and Sixty-four, Ninety-four! -- London : Chatto & Windus, 1926.

R. H. Mottram (1883-1971) -- standing left -- with Claims Commission colleagues. From The flower of battle : British fiction writers of the First World War by Hugh Cecil. -- London : Secker & Warburg, c1995

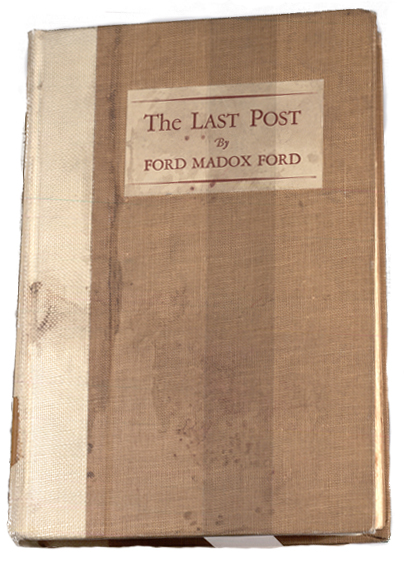

The Last Post : a Novel / by Ford Madox Ford. -- New York : A. & C. Boni, c1928.

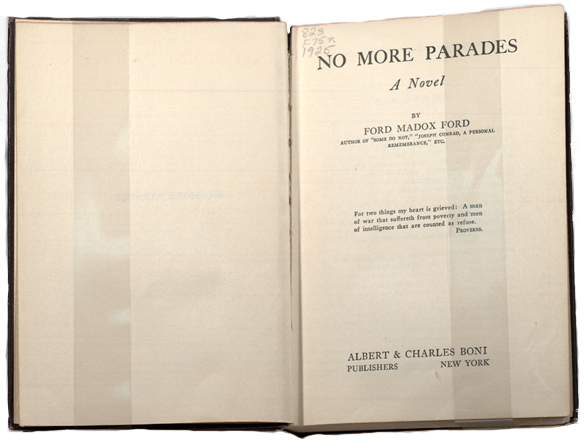

No More Parades, a Novel by Ford Madox Ford... -- London, Duckworth, <1925>

Prolific author, Ford Madox Hueffer -- later Ford Madox Ford -- (1873-1939), grandson of the pre-Raphelite painter Ford Madox Brown (for whom FMF modelled), wrote the finest work of fiction about the Great War: the story of the character Christopher Tietjens in the trilogy Parade's End (actually, the work is sometimes considered a tetralogy -- there is much debate over the value/relationship of a fourth volume, Last Post -- and William Carlos Williams declared that the four novels "constitute the English prose masterpiece of their time" (Bergonzi 168). Ford was 41-years old when he enlisted and served as a subaltern on the Somme (where he was gassed). Ford had already done quite a bit of living and writing when the war begin, and the regimentation and simple, singularity of purpose of Army life gave Ford an unexpected freedom and peace that he had never known in his always-tempestuous pre-war life. Ford, an early proponent of impressionism, a close friend of Joseph Conrad, also wrote one of the great novels of the 20th-Century: The Good Soldier : a Tale of Passion (1915) -- the first chapters of which were published in Wyndham Lewis' BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex.

A Man Could Stand Up : a Novel /by Ford Madox Ford. -- London : Duckworth, 1926.

No More Parades, a Novel by Ford Madox Ford... -- London, Duckworth, <1925>

Some Do Not : a Novel / by Ford Madox Ford, author of "The Marsden Case," "Mister Bosphorus and the Muses," etc., etc. -- London : Duckworth and Company, 1924.

Death of a Hero : a Novel / by Richard Aldington. -- New York : Covici, Friede, 1929 (New York : Van Rees Press)

Richard Aldington (1892-1962), one of the 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone in Westminster Abbey, also wrote a bitter novel about the war. The Lee Library holds copies of both the American edition of Death of a Hero (1929) -- displayed -- and the British: Death of a Hero : a Novel / by Richard Aldington. -- London : Chatto and Windus, 1929. Bernard Bergonzi describes Death of a Hero as "a massive ejaculation of pent-up venom" (p. 173). In the novel, Aldington attacks the system that allowed and then furthered the war: Victorianism and the Army High Command, etc. The novel is near to autobiography, including such characaters as Elizabeth who is remarkably like Aldington's wife, the American poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle).

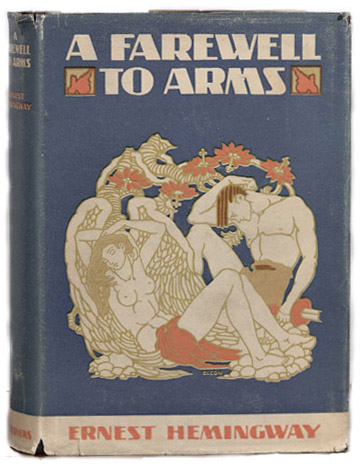

A Farewell to Arms / by Ernest Hemingway. -- New York : Grosset & Dunlap, Publishers, 1929.

A Farewell to Arms is a tragic love story between Frederic Henry, an American fighting in the Italian Army, and Catherine Barkley, an English nurse. Its author, Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was a volunteer ambulance driver in the Great War-- along with other Americans such as John Dos Passos, Malcolm Cowley, Dashiell Hammatt, and e.e. cumming. Walt Disney had finished stateside training, and was on his way to France when the war ended (over half a century later, during often hotly contested negotiations to build Euro-Disney, the Disney Corporation used their founder's service to France in an attempt to improve PR). Arlen J. Hansen's Gentlemen Volunteers: The Story of the American Ambulance Drivers in the Great War, August 1914 -- September 1918 would be a fascinating companion to Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms.

Journey's End: A Play in Three Acts / by R. C Sherriff. -- New York, Bretano's Publisher's, 1929.

R. C. Sherriff (1896-1975) wrote one of the most famous dramas about the Great War: Journey's End. The play takes place in the trenches and dugouts near St. Quentin in the last year of the war, in March 1918, just prior to the German offensive. Journey's End (first performed in 1928), and the subsequent motion picture, enjoyed such popularity that its depiction of Great War trench life has become almost cliche (recently parodied by Rowan Atkinson in Blackadder Goes Forth): talk of Rugger and cricket, public schools and social class; and drinking and dispair offset by displays of calm, dutiful, even cheerful self-sacrifice.

The Middle Parts of Fortune : Somme & Ancre, 1916. -- <London> : The Piazza Press : Issued to subscribers by Peter Davies, 1929.

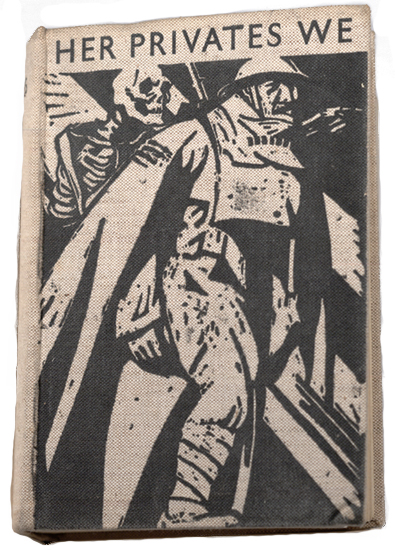

Her Privates We / by Private 19022. -- London : Peter Davies, 1930.

Frederic Manning (1882-1935) wrote the "best book about ordinary soldiers in the Great War" (Stephen, Never Such Innocence, 341). Entitled either The Middle Parts of Fortune : Somme & Ancre, 1916 (1929) for the unexpurgated version, or Her Privates We (1930) for the bowdlerized and more well-known version, and issued anonymously -- that is, by "Private 19022" -- Bernard Bergonzi compares its "austere concentration on the soldier's existence at or near the Front" to Edmund Blunden's Undertones of War (181). Manning's name did not appear on Her Privates We until 1943 -- eight years after his death; however, T. E. Lawrence ("of Arabia"), an admirer of the book (and Manning's earlier work), recognized Manning as the author (Stephen, Never Such Innocence, 341).

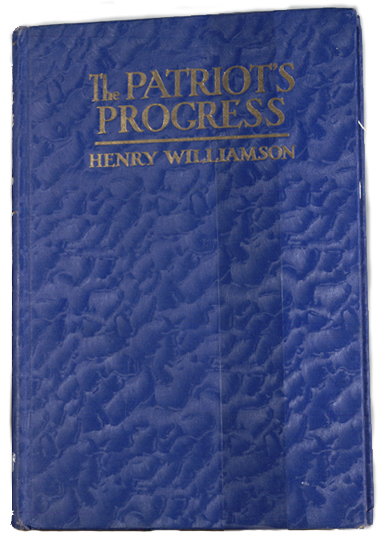

The Patriot's Progress : Being the Vicissitudes of Pte. John Bullock / related by Henry Williamson and drawn by William Kermode. -- London : Geoffrey Bles, 1930.

Henry Williamson (1895-1977) actually wrote his autobiographical novel (note another allusion to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress), The Patriot's Progress : Being the Vicissitudes of Pte. John Bullock (1930), to accompany a series of woodcuts by Australian artist William Kermode. The woodcuts are stark, loveless haunting vignettes of army and Front Line life. Rather than reach the Celestial City, as Bunyan's Christian, Williamson's character, John Bullock survives four years in the trenches, but loses a leg. The novel is "savagely satirical," and much of Williamson's grist for his outlook came from his participation in the famous, informal, spontaneous Christmas truce of 1914, which convinced him that German and English soldiers were essentially brothers and shouldn't fight (Bergonzi 183-184). (For more about this Christmas truce, see Michael Forman's War Game.)

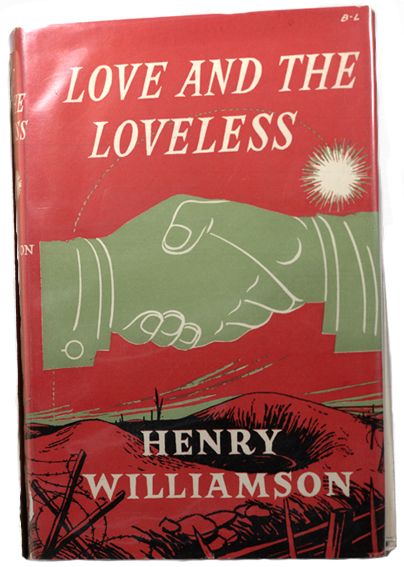

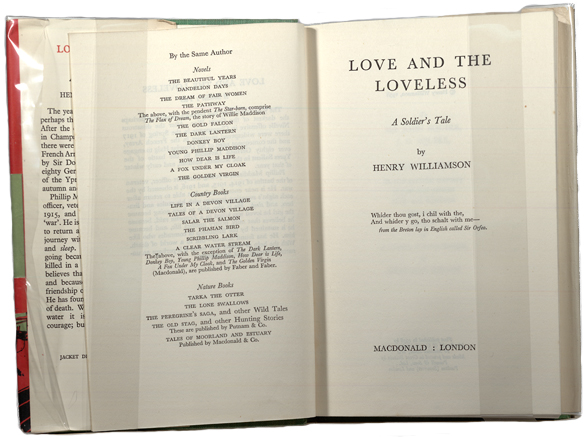

Love and the Loveless : a Soldier's Tale (1958) is one of five autobiographical novels Williamson wrote in the 1950's looking back on his experience in the Great War: How Dear is Life (1954), A Fox Under My Cloak (1955), The Golden Virgin (1957), Love and the Loveless (1958), and A Test to Destruction (1960) -- these five being part of Williamson's larger autobiographical series, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (Bergonzi 184).

Love and the Loveless : a Soldier's Tale / by Henry Williamson. -- London : MacDonald, c1958.

Memoirs

" . . . to me, the War was inevitable and justifiable. Courage remained a virtue. And that exploitation of courage, if I may be allowed to say a thing so obvious, was the essential tragedy of the War, which, as everyone now agrees, was a crime against humanity." Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967)

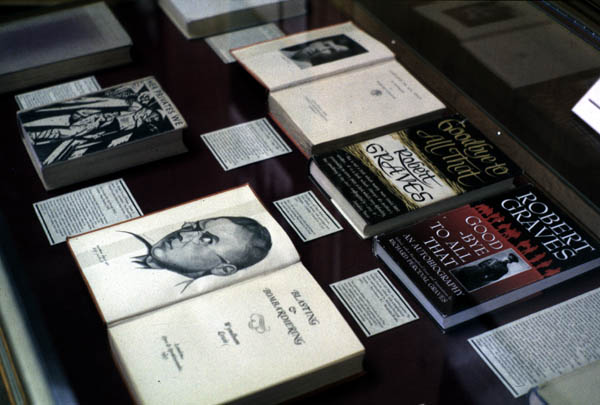

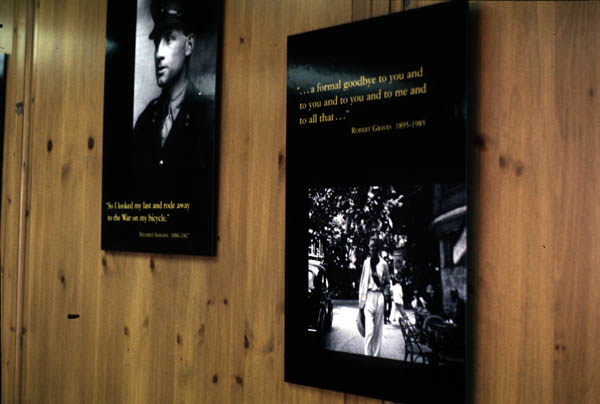

Works of fiction about the war had been coming out since the early 20's. Some 10 years after the Armistice, writers who had fought in the war began to publish their memoirs. The best came from three writers who would also be remembered as poets: Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, and Siegfried Sassoon.

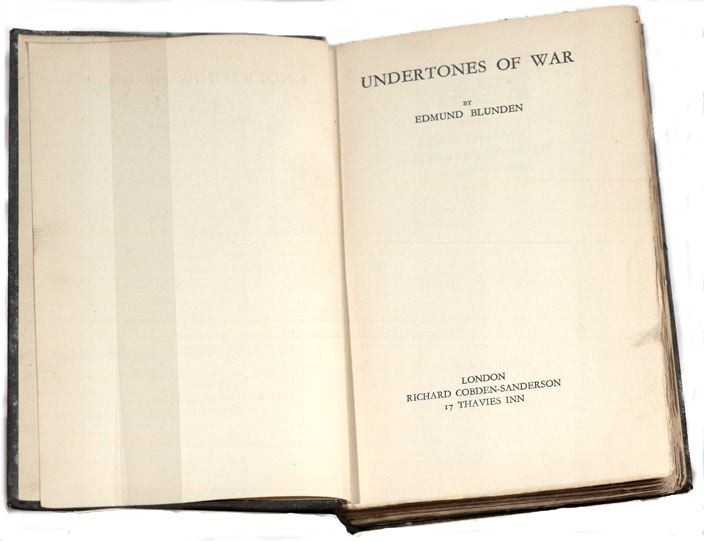

Undertones of War / by Edmund Blunden. -- London : R. Cobden-Sanderson, 1928.

Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) described himself, on the last page of his memoir Undertones of War (1928), as "a harmless young shepherd in a soldier's coat" (p. 314). Undertones of War, understated, and filtered through Blunden's gentle pastoralism , ranks with Goodbye to All That (1929) by Robert Graves, and The Memoirs of George Sherston (1928, 1930, 1936) by Siegfried Sassoon "as among the finest prose works by a Great War poet" (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 331).

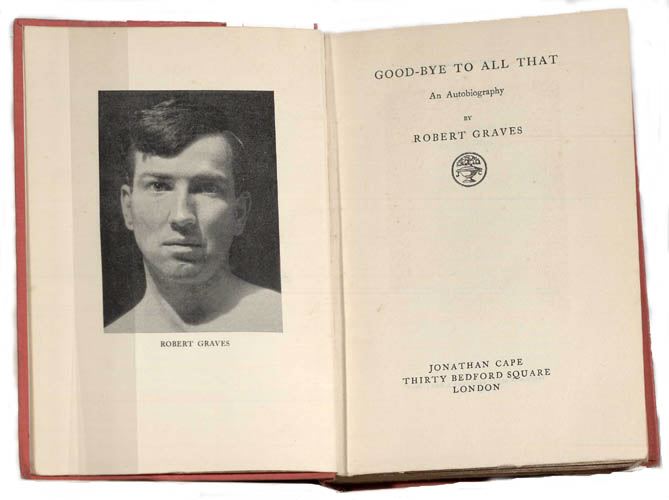

Good-bye to All That : An Autobiography / by Robert Graves. -- London : J. Cape, 1929.

Although Robert Graves (1895-1985), one of the 16 Great War poets commemorated in Westminster Abbey, also wrote one of the most famous memoirs of the war. Graves' "autobiography," Good-bye to All That, dashed off during the summer of 1929, is an extremely entertaining, amusing, even chatty story that begins with Graves' experience in public school (Charterhouse), through his experiences on the Western Front (including being reported dead when severely wounded, and coming to the rescue of a sure-to-be-court-martialed Siegfried Sassoon), and finally to his (attempted) readjustment after the war. The more careful memoirists, Blunden and Sassoon (a fellow officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers), as well as Graves' RWF Commander, went through the book noting all the errors, of which they found many.

Goodbye to All That / Robert Graves. -- New edition, revised, with a prologue and epilogue. -- London : Cassell & Co. Ltd., 1957.

This (1957 ed.) is the edition used until recently by many critics, including Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory.

Good-bye to All That : an Autobiography / by Robert Graves ; edited, with a biographical essay and annotations by Richard Perceval Graves. -- Providence, R.I. : Berghahn Books, 1995.

The definitive edition (1995) of Goodbye to All That, edited by Graves' nephew (for the centenary of Graves' birth), integrating earlier editions (1929 and 1957), comparing additions and deletions, and providing extensive footnotes and precise chronology.

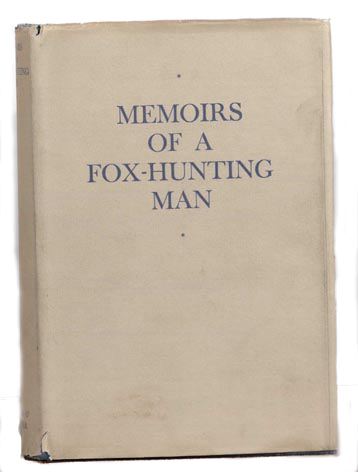

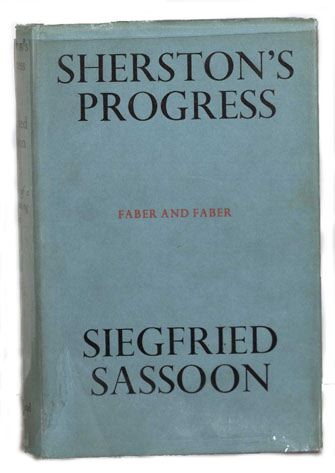

Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man / by Siegfried Sassoon. -- <1st ed.> -- London : Faber & Gwyer, 1928.

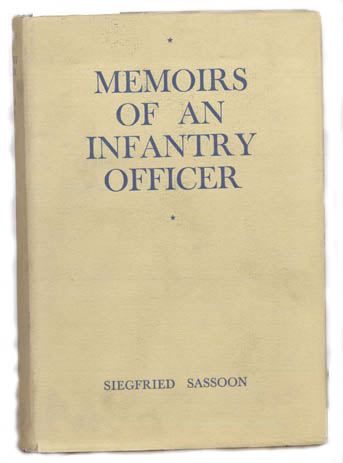

Memoirs of an Infantry Officer / by the author of Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man. -- London, Faber & Faber limited <1930>

Sherston's Progress / by Siegfried Sassoon. -- 1st ed. -- London : Faber and Faber Limited, 24 Russell Square, CMXXXVI.

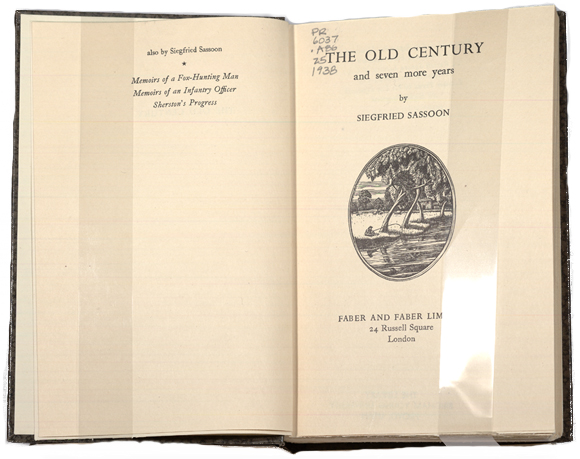

One of the most famous Great War poets, Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) spent over twenty years reliving his life before, during, and after the war in six volumes of (barely fictionalized) memoir and (more straightforward) autobiography. Sassoon described himself as an "Enoch Arden," compelled to revisit old haunts and walk over the ground again and again. In his first three volumes, collectively titled The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston (1937), Sassoon employed a fictional, less complicated version of himself to tell his story. Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928) covers Sassoon's (that is, George Sherston's) privileged early life as a budding young country gentleman and fox-hunter, his enlistment in 1914, and return home on leave in 1916 before the Battle of the Somme. Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) continued the story of George Sherston in the war: the Battle of the Somme, getting wounded in 1917, being sent to "Slateford" -- Craiglockhart Hospital. In 1936, Sassoon's only child, a son was born -- of course he named him "George." The final volume in the trilogy, Sherston's Progress (1936) -- note the allusion to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress -- takes up the story at Craiglockhart Hospital, especially Sassoon/Sherston's relationship with neurologist W.H.R. Rivers (for a 1990's fictional account, see also Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy). Sherston's Progress ends with Sassoon/Sherston sent back to the front, where he is wounded again and sent back to England, where the last scene is a visit from Rivers (the only "real-life" character in the trilogy whose name, probably because of its natural associations with calm, rest, and "hydrotheraphy," remains unchanged -- for instance, Robert Graves appears as David Cromlech, and David Thomas, a close friend of Graves' and Sassoon, as Dick Tiltwood). There is no mention in Sherston's Progress of Wilfred Owen, and/or their meeting and friendship while at Craiglockhart Hospital -- although this is entirely due to Sassoon's modesty (for dramatic/fictional accounts of their friendship, see Stephen MacDonald's Not About Heroes : the Friendship of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen and Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy).

Once he'd finished The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston (1937), Sassoon immediately began on a more straightforward autobiography (again in three volumes): The Old Century and Seven More Years. -- London, Faber and Faber limited <1938>, covers the end of the Nineteeth Century through 1907; The Weald of Youth. -- London : Right Book Club, <1943>, continues the picture of the idyllic, prelapsarian days before the war; and Siegfried's Journey, 1916-1920. -- London : Faber and Faber Limited, 1945, takes Sasson through the war and his first years afterwards in readjustment. In addition, the 1980's, saw yet a third trilogy covering this portion of Sassoon' life (Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy, in the 1990's, would be the fourth): Siegfriend Sassoon Diaries, 1920-1922 (1981); Siegfried Sassoon Diaries, 1915-1918 (1983); and Siegfried Sassoon Diaries, 1923-1925 (1985).

Helen Thomas (1877-1967), wrote her 2-volume autobiography, As It Was and World Without End, about her life with Great War poet Edward Thomas -- their ups and downs as Edward struggled to make his own way as a freelance writer doing hack work and book reviews. The Thomas' knew Wilfrid Wilson Gibson and his family, as well as the Robert Frosts' who came over from the United States. It was Robert Frost who encouraged Edward toward poetry -- where, in the brief period before his death, he finally found his rightful niche as a writer. Thomas was killed on 9 April 1917, at the Battle of Arras. Edward Thomas' struggle to find his voice as a poet, as well as his subsequent poetry has impressed, among many others, Second World War poet Alun Lewis and contemporary poet Leslie Norris.

As It Was / by H. T. -- 1st ed; 2nd issue. -- London, W. Heinemann ltd., 1926.

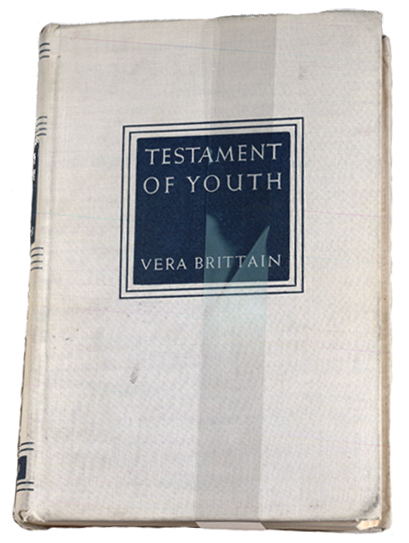

Testament of Youth : an Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925/ by Vera Brittain. -- London : Victor Gollancz, 1933.

Vera Brittain (1893-1970) served as a V.A.D. (Volunteer Aid Detachment) nurse during the war. In 1915, she became engaged to Roland Aubrey Leighton (1895-1915). Tragically, Leighton was wounded in a midnight action and died on December 23, 1915, the day before he was to rotate to England on Christmas leave (Vera thought that the phone call on December 27th must be Roland calling to tell her that he had arrived in England). Roland Aubrey Leighton has since become known as a Great War poet based primarily on the poems that he wrote to Vera Brittain. Vera also lost her brother, killed in the last year of the war. Four days before her brother's death, Vera wrote a poem (she was also quite a good poet) for her brother (dedicating it to the memory of July 1, 1916 -- the first day of the Battle of the Somme) that begins "Your battle-wounds are scars upon my heart." Catherine Reilly used that image for the title of her anthology Scars Upon My Heart : Women's Poetry and Verse of the First World War.

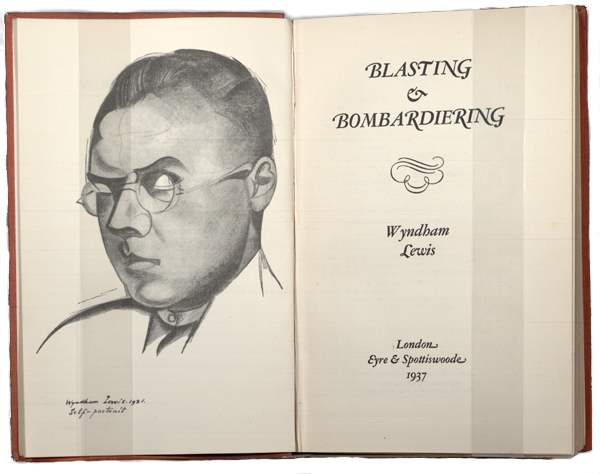

Blasting & Bombardiering. -- London : Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937.

Artist, "Vorticist" (see also Lewis' avant garde magazine BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex), and all-around radical, Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) recorded his experiences as an artilleryman in the Great War in his autobiography Blasting & Bombardiering (1937). As an official war artist, Lewis also painted remarkable scenes of artillery in action during the Great War. A prolific writer, as well as an innovative, geometrical artist, Lewis also wrote poems, dramas, volumes of art criticism, and in the late 30s, exposés warning about Adolf Hitler.

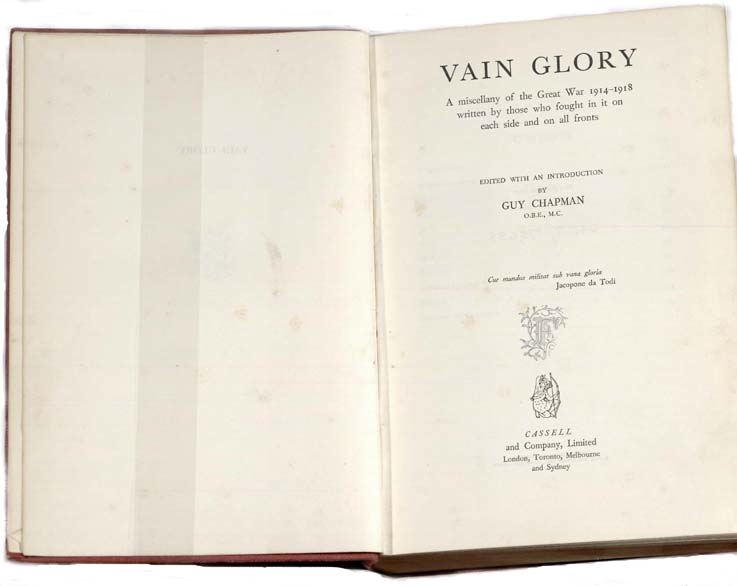

Vain Glory : A miscellany of the Great War, 1914-1918, written by those who fought in it on each side and on all fronts, edited with an introduction by Guy Chapman. -- London, Cassell and Company, limited [1937]

An anthology of memoirs, poems, and personal accounts of the Great War, including selections by Edmund Blunden,Vera Brittain, Wilfrid Gibson, Robert Graves, Patrick MacGill, Frederick Manning, R. H. Mottram, Wilfred Owen, Herbert Read, Isaac Rosenberg, Owen Rutter, Siegfried Sassoon, Alan Seeger, Charles Sorley, and Henry Williamson, as well as Sylvia Pankhurst, Ernst Jünger, and Benito Mussolini.