Influences on Great War Literature

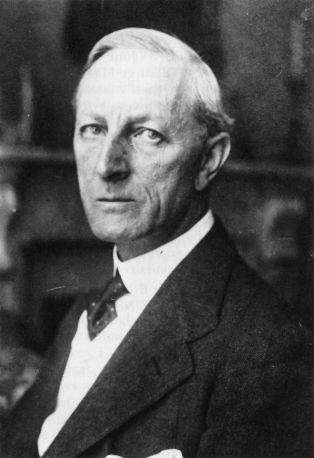

"Play up! play up and play the game!" Sir Henry Newbolt (1862-1938)

Because this is an exhibit of the Lee Library's holdings in Great War literature, the examples of works listed below are not all first editions, but where possible I've tried to exhibit an edition that would've been available to readers at the time preceding and during the Great War.

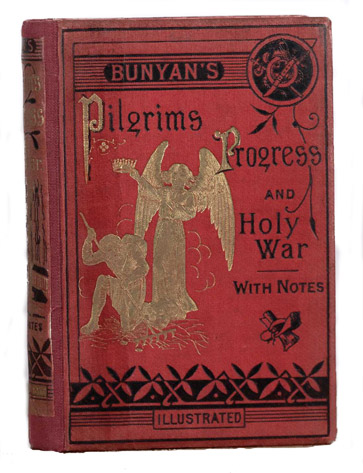

The Pilgrim's Progress, and, Holy War /by John Bunyan ; with memoir of the author. -- London : W. Leigh, <188-?>

First published in 1678 (with part 2 in 1684), The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come, Delivered under the Similitude of a Dream Wherein Is Discovered, the Manner of His Setting Out, His Dangerous Journey, and Safe Arrival at the Desired Countrey by John Bunyan (1628-1688), was known and read in almost every English-speaking home before the Great War. Its images were invoked frequently by soldiers in the trenches: the "Slough of Despond," the "Valley of the Shadow of Death," and "a man clothed in rags . . and a great burden upon his back." (See Pilgrimage : Poems by Eric Shepherd, and The Anzac Pilgrim's Progress : Ballads of Australia's Army by Lance-Corporal Cobber for examples of Great War works influenced by Bunyan.)

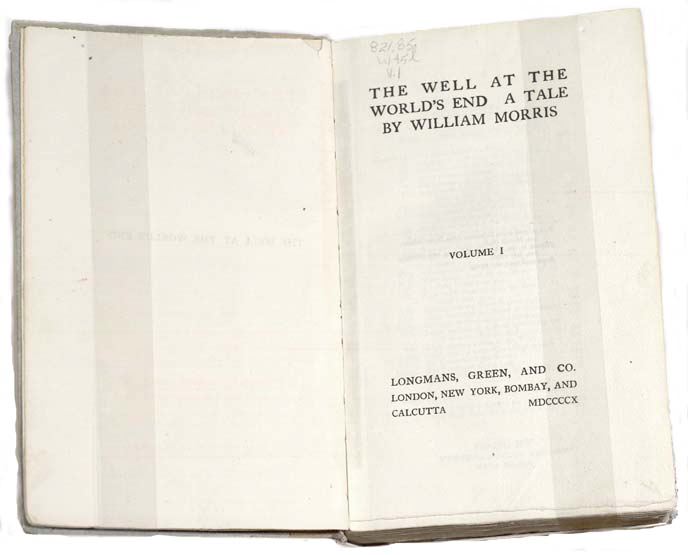

The Well at the World's End: a Tale / by William Morris. -- London ; New York : Longmans, Green, 1910.

A "Victorian pseudo-medieval romance" (Fussell, 135) first published in 1896, The Well at the World's End by William Morris (1834-1896) tells the story of "young Prince Ralph's adventures in search of the magic well at the end of the world, whose water have the power to remove the scars of battle" (135-36).

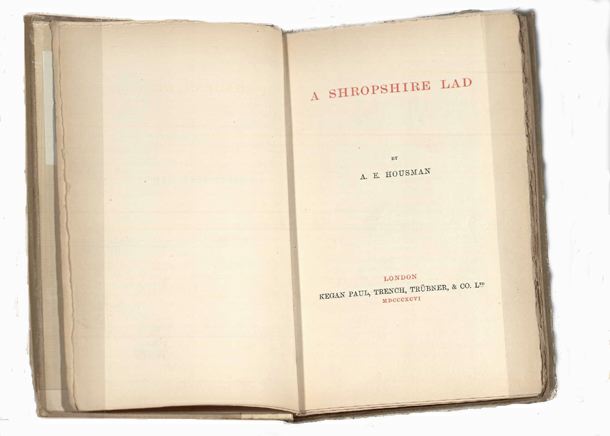

A Shropshire Lad / by A.E. Housman. -- London : K. Paul Trench, Truber & Co., 1896.

With epigrammatic poems replete with handsome, young, doomed athletes and soldiers, A Shropshire Lad by A. E. (Alfred Edward) Housman (1859-1936), influenced Great War poets such as Wilfred Owen -- himself a "Shropshire lad" from Oswestry. Examples of the many soldier-lads poems in A Shropshire Lad are XXXV, and LVI ("The Day of Battle").

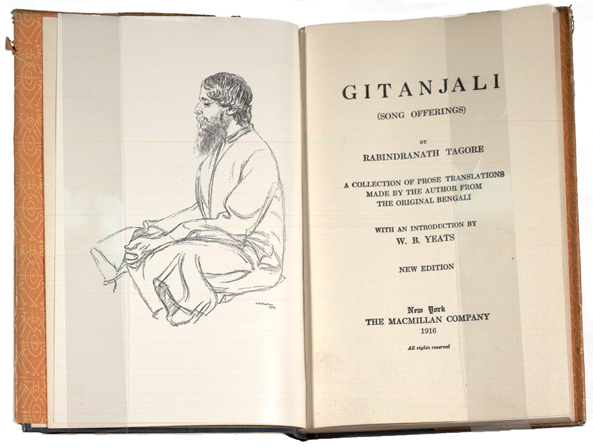

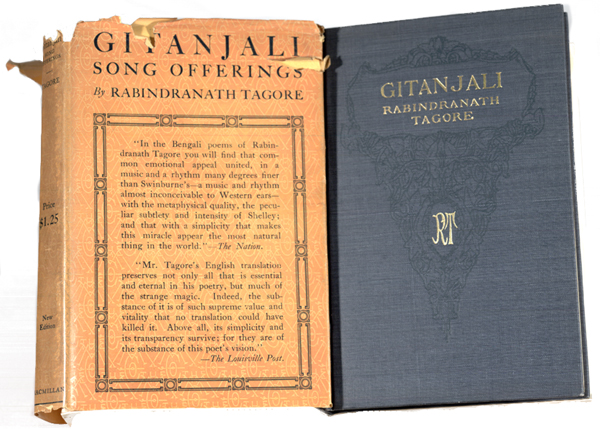

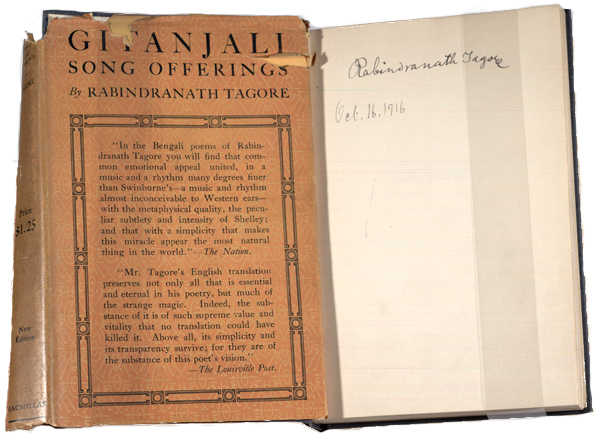

Gitanjali (song offerings) / by Rabindranath Tagore : A collection of prose translations made by the author from the original Bengali. With an introduction / by W.B. Yeats. New Edition. New York : The Macmillan Company, 1916.

Born in (then British) Calcutta, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was an actor, playwright, painter, novelist and poet (among other things). In 1913, Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for his collection of poetry entitled Gitanjali (from the Bengali, meaning "song offerings") which he had translated into English in 1910. W. B. Yeats added his approval in the his introduction. Wilfred Owen read Tagore, and in a letter home quoted from song #96: " . . . what I have seen is unsurpassable." At least one recent critical work on Owen has seen this same phrase as becoming Owen's unique theme as he progressed as a war poet.  The amazingly perceptive Sebastian Faulks included this same first line from song #96 ("When I go from hence let this be my parting word, that what I have seen is unsurpassable") as context for his contemporary novel of the Great War, Birdsong (1996). Tagore also had his anti-fans: by 1914, his poetry had become so popular and pervasive that Wyndham Lewis included him in his list of the infamous in BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex, along with Clan Strachey, Dean Inge (see Rupert Brooke), Galsworthy, the Post Office, and Codliver Oil (p. 21). The Lee Library has a copy of Gitanjali autographed by the author: "Rabindranath Tagore, Oct 16, 1916."

The amazingly perceptive Sebastian Faulks included this same first line from song #96 ("When I go from hence let this be my parting word, that what I have seen is unsurpassable") as context for his contemporary novel of the Great War, Birdsong (1996). Tagore also had his anti-fans: by 1914, his poetry had become so popular and pervasive that Wyndham Lewis included him in his list of the infamous in BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex, along with Clan Strachey, Dean Inge (see Rupert Brooke), Galsworthy, the Post Office, and Codliver Oil (p. 21). The Lee Library has a copy of Gitanjali autographed by the author: "Rabindranath Tagore, Oct 16, 1916."

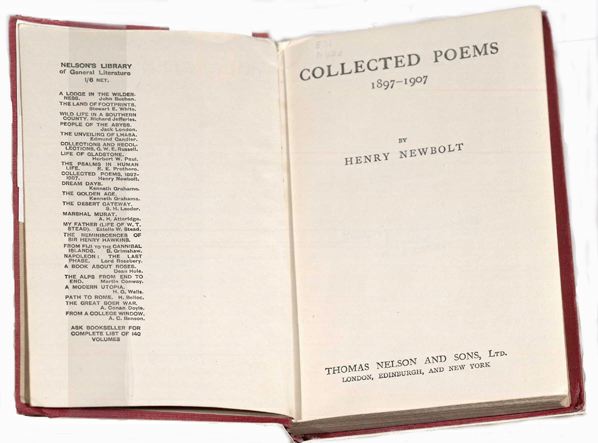

Collected poems, 1897-1907 / by Henry Newbolt. -- London ; Edinburgh ; New York : T. Nelson & Sons, Ltd., <1910?>

Sir Henry Newbolt (1862-1938) was one of the Edwardian "Great Men," and a close friend of General Sir Douglas Haig, whom he "first met when they were students together at Clifton College, whose cricket field provides the scene of Newbolt's first stanza [of his poem "Vitai Lampada"]" (Fussell, 26). Newbolt's belief in the values inculcated in the public schools, the virtues of self-abnegation, good sportsmanship, and "playing the game" (whether in life or in battle) is dramatized in poems such as "Vitai Lampada" ("They Pass on the Torch of Life") -- written before the war, but seemingly anticipating the coming need for selfless sacrifice for loyalty and duty. (The falling torch image in "Vitai Lampada" also appears in John McCrae's famous "In Flanders Fields.") Another "sporting" poem of the war is the anonymous "Cricketeers of Flanders." (For this "sportsmanship" mentality taken to its illogical extreme -- that is, to kicking soccer balls toward the "goal" of the enemy trenches -- click here to see Paul Fussell's account in The Great War and Modern Memory; see also Michael Foreman's War Game for a children's book on the subject).

Sir Henry Newbolt (1862-1938) was one of the Edwardian "Great Men," and a close friend of General Sir Douglas Haig, whom he "first met when they were students together at Clifton College, whose cricket field provides the scene of Newbolt's first stanza [of his poem "Vitai Lampada"]" (Fussell, 26). Newbolt's belief in the values inculcated in the public schools, the virtues of self-abnegation, good sportsmanship, and "playing the game" (whether in life or in battle) is dramatized in poems such as "Vitai Lampada" ("They Pass on the Torch of Life") -- written before the war, but seemingly anticipating the coming need for selfless sacrifice for loyalty and duty. (The falling torch image in "Vitai Lampada" also appears in John McCrae's famous "In Flanders Fields.") Another "sporting" poem of the war is the anonymous "Cricketeers of Flanders." (For this "sportsmanship" mentality taken to its illogical extreme -- that is, to kicking soccer balls toward the "goal" of the enemy trenches -- click here to see Paul Fussell's account in The Great War and Modern Memory; see also Michael Foreman's War Game for a children's book on the subject).

Satires of Circumstance <Poems> The Complete Poetical Works of Thomas Hardy / edited by Samuel Hynes. -- Oxford <Oxfordshire> : Clarendon Press ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1982-

Published in November, 1914, but containing poems written before the war (some as far back as 1870), Satires of Circumstance by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), uncannily foretold, in such poems as "Channel Firing," and "Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?," of the irony and disappointment that the war would bring. Hardy's most famous poem about the Great War, "Men Who March Away", which first appeared in The Times (as "The Song of the Soldiers"), was published in Moments of Vision (1917).

The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 / chosen and edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press ; London ; New York : H. Milford, 1915.

Printed on India Paper, this compact-size edition of the Oxford Book of English Verse was carried in the war by soldiers who alluded to its well-known lines in their diaries, their letters home, and in their own poetry. "Indeed, the Oxford Book of English Verse presides over the Great War in a way that has never been sufficiently appreciated" says Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory, 159). It is this edition of the Oxford Book of English Verse that John Ball reads in David Jones' In Parenthesis -- specifically William Dunbar's "Lament for the Makers."