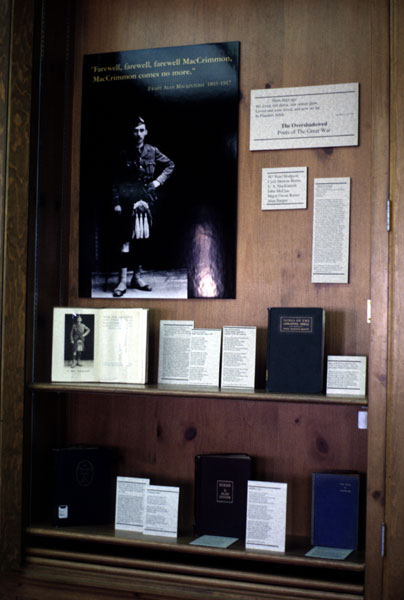

The Overshadowed Poets of The Great War

. . . Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields. John McCrae (1872-1918)

. . . Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields. John McCrae (1872-1918)

William Noel Hodgson was a Georgian poet in the style of Rupert Brooke. He volunteered in 1914, and served with the Devonshire Regiment. In September, 1915, during the Battle of Loos, "[u]nder heavy enemy fire Hodgson, three other young officers and a hundred men held a captured trench for 36 hours without reinforcements or food. Hodgson was awarded the Military Cross" (Powell, A Deep Cry 99). Marching out of this hell-hole, Hodgson composed the incredibly resilient "Back to Rest." In 1916, Hodgson began writing stories, poems, and essays about the front under the pseudonym "Edward Melbourne." Hodgson was especially fond of telling tales about his resourceful "batman" (his aide). His pieces enjoyed an audience in the leading magazines of the day. As his unit waited to move up to its jumping off position at the Somme Offensive, Hodgson composed his last poem "Before Action." On July 1st, Hodgson's battalion attacked the German trenches south of Mametz. "At the end of the day the bodies of 159 men, including Noel Hodgson were found. The body of Hodgson's batman was lying at his side. The men of the 9th Battalion were buried in their Mansel Copse trench, and a notice above the trench read: "The Devonshires held this trench. The Devonshires hold it still" (Powell, A Deep Cry105).

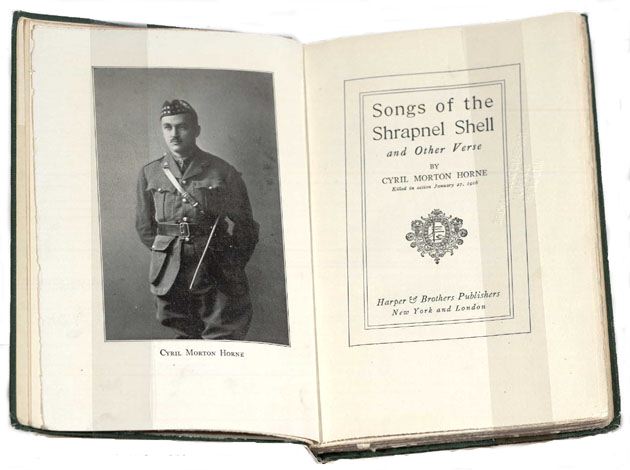

Songs of The Shrapnel Shell, and Other Verse / by Cyril Morton Horne. -- New York and London : Harper & brothers, <c1918>.

"When the war broke out Cyril Horne (1887-1916), who had written an opera, was working in the American theatre" (Powell, A Deep Cry 53). He was commissioned in March 1915, survived the Battle of Loos (September 1915), but was killed in an artillery barrage on January 27th, 1916. Coincidentally, the collection of Horne's poetry published after his death is entitled Songs of the Shrapnel Shell and Other Verse.

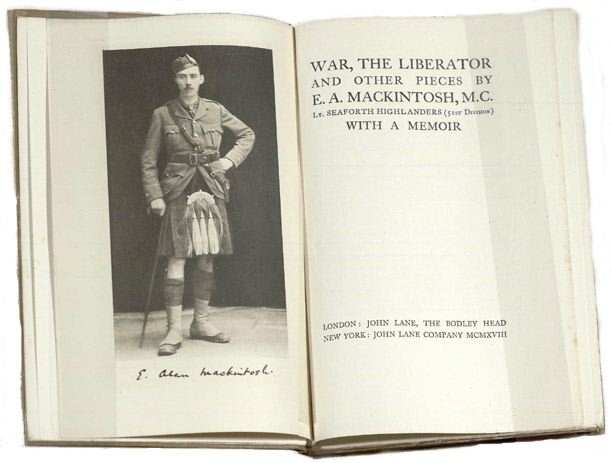

War, The Liberator, and Other Pieces, by E.A. Mackintosh, M.C., lt. Seaforth Highlanders (51st division) ; with a memoir. -- London, John Lane ; New York, John Lane company, 1918.

E. A. Mackintosh (1893-1917) served as an officer in the Seaforth Highlanders from December 1914. He played the pipes, spoke Gaelic, and was loved by his men who affectionately called him "Tosh." For his part, Mackintosh returned that love. On May 16th, 1916, he carried wounded Private David Sutherland through 100 yards of German trenches with the Germans in hot pursuit. However, before Mackintosh could bring him to friendly trenches, Private Sutherland died and his body had to be left behind. Mackintosh's bravery would win him the Military Cross, and in memory of Private David Sutherland, and in recognition of his unique role as 23-year old "father" to his men, he wrote "In Memoriam." In August 1916, after being wounded and gassed at High Wood on the Somme, Mackintosh wrote "To the 51st Division: High Wood, July -- August 1916." During his recovery and rotation to England, Mackintosh became engaged. In October 1917, Mackintosh returned to France, and on the second day of the Battle of Cambrai, November 21, 1917, was killed. He was 24. In "Cha Till Maccrimmein" -- a poem once considered by Scottish enthusiasts to be an authentic Highland lament -- Mackintosh foretells his own death.

E. A. Mackintosh (1893-1917) served as an officer in the Seaforth Highlanders from December 1914. He played the pipes, spoke Gaelic, and was loved by his men who affectionately called him "Tosh." For his part, Mackintosh returned that love. On May 16th, 1916, he carried wounded Private David Sutherland through 100 yards of German trenches with the Germans in hot pursuit. However, before Mackintosh could bring him to friendly trenches, Private Sutherland died and his body had to be left behind. Mackintosh's bravery would win him the Military Cross, and in memory of Private David Sutherland, and in recognition of his unique role as 23-year old "father" to his men, he wrote "In Memoriam." In August 1916, after being wounded and gassed at High Wood on the Somme, Mackintosh wrote "To the 51st Division: High Wood, July -- August 1916." During his recovery and rotation to England, Mackintosh became engaged. In October 1917, Mackintosh returned to France, and on the second day of the Battle of Cambrai, November 21, 1917, was killed. He was 24. In "Cha Till Maccrimmein" -- a poem once considered by Scottish enthusiasts to be an authentic Highland lament -- Mackintosh foretells his own death.

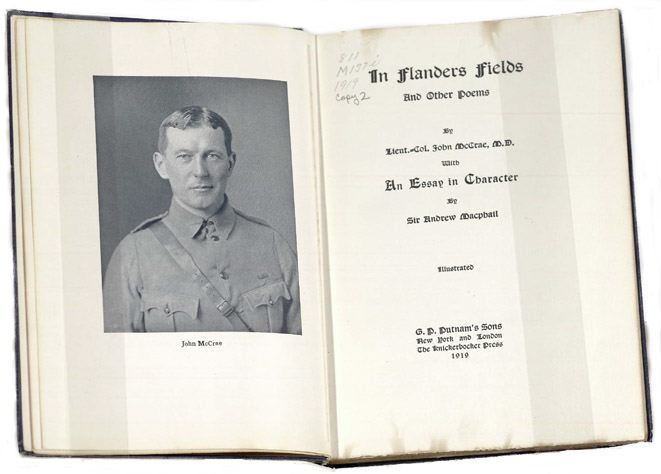

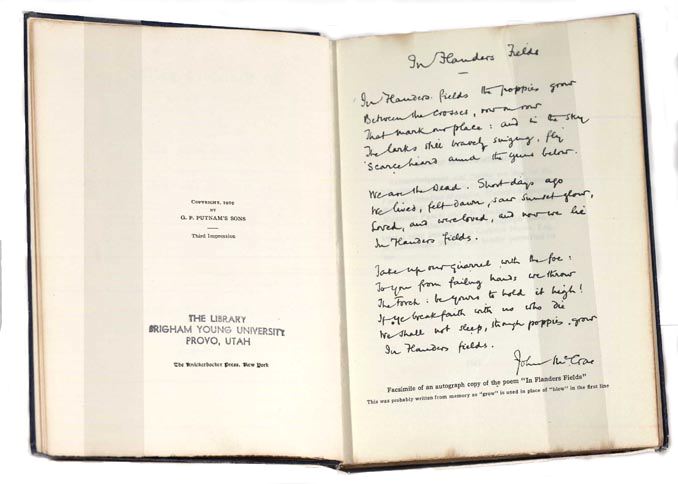

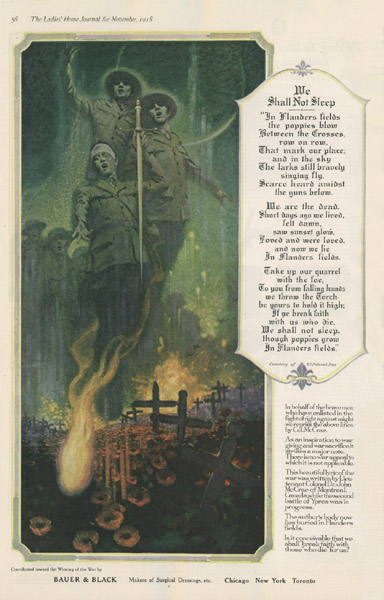

In Flanders Fields, and Other Poems, by Lieut.-Col. John McCrae, M. D., with an essay in character, by Sir Andrew Macphail ... -- New York, London, G. P. Putnam's sons, 1919.

John McCrae (1872-1918), a Canadian physician, wrote what became the most famous poem of the Great War, "In Flanders Fields." (Compare with Isaac Rosenberg's poem "Break of Day In The Trenches" -- considered by most critics to be the greatest poem of the war.) Written in early May 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, it was an instant hit after appearing in the December 8th issue of Punch. The poem arrived with the same timeliness as Rupert Brooke's sonnets ("I. Peace," and "V. The Soldier") had done a year earlier. It struck a ready nerve in many readers, and was "answered" -- politely parodied -- by would-be poets on both sides of the Atlantic (including even in the Relief Society Magazine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah). LTC John McCrae continued to serve until overworked and demoralized, he died of pneumonia on the 28th of January, 1918, at age 45.

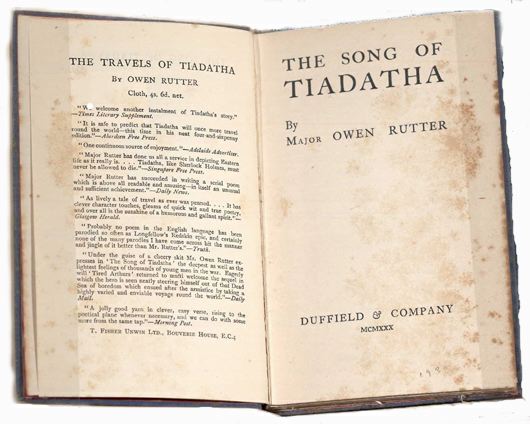

Song of Tiadatha / by Major Owen Rutter. -- [New York] : Duffield & Company, MCMXXX.

(Copy on loan to the Harold B. Lee Library.)

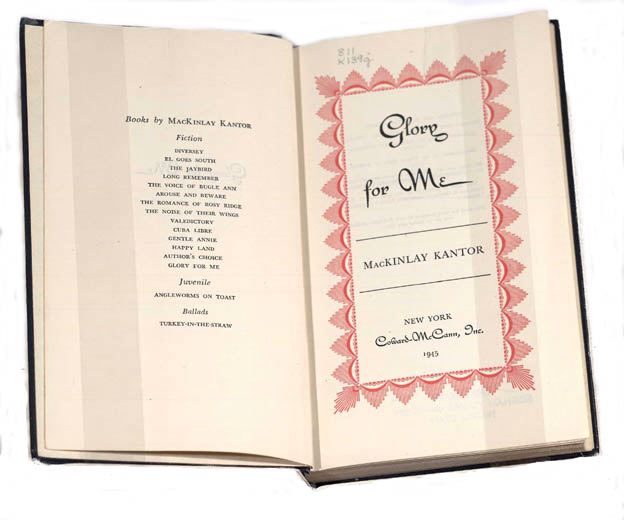

Glory For Me / MacKinlay Kantor. -- New York : Coward-McCann, 1945.

Major Owen Rutter (1889-1944), using the pseudonym "Klip-Klip," wrote one of the masterpieces of Great War verse. A parody of Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha, entitled Song of Tiadatha (1919, 1920); a book-length tale of one Tiadatha, a rather naive, privileged young man, and his transformation through his war experiences. Song of Tiadatha enjoyed success, and was followed by Travels of Tiadatha (1922). (See also David Jones' In Parenthesis for an example of an epic poem from the Great War, and MacKinlay Kantor's Glory for Me for an example of a narrative poem from the Second World War -- eventually produced as the 1946 motion picture The Best Years of Our Lives: Glory For Me / MacKinlay Kantor. -- New York : Coward-McCann, 1945.)

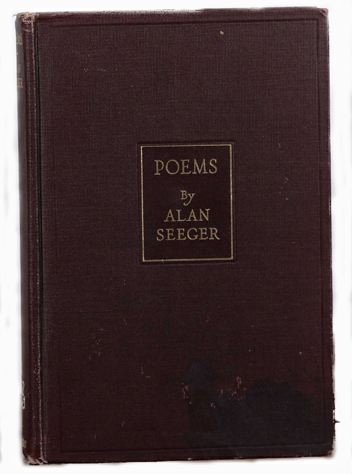

Poems / by Alan Seeger ; with an introduction by William Archer. -- New York : C. Scribner's Sons, c1916.

Alan Seeger (1888-1916) has been called "the American Rupert Brooke" (Holt, 94). Educated at Harvard, he lived in Paris before the war. When war came, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion, and in the Spring of 1916, wrote his famous poem "I Have A Rendezvous With Death." Seeger was mortally wounded on the 4th of July, 1916, at the Battle of the Somme. For Americans, the popularity of Seeger's "I Have A Rendezvous With Death" was second only to John McCrae's "In Flanders Fields," and the poem "enjoyed" parodies and responses as did McCrae's poem.

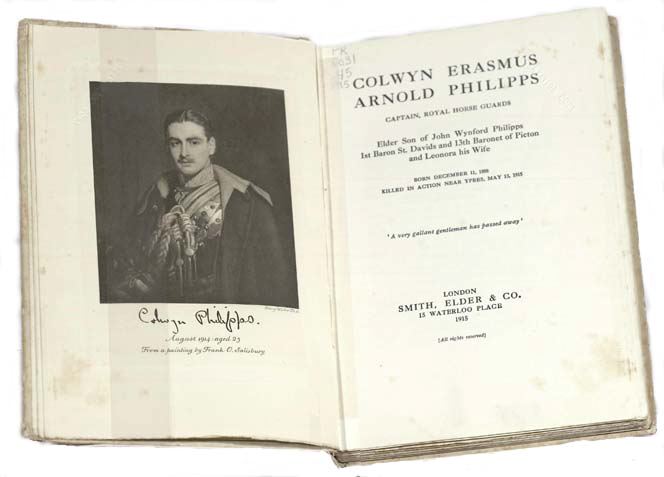

Colwyn Erasmus Arnold Philipps, captain, Royal Horse Guards, elder son of John Wynford Philipps, lst baron St. Davids and 13th baronet of Picton and Leonora his wife, born December 11, 1888, killed in action near Ypres, May 13, 1915. -- London : Smith, Elder, 1915.

Posthumously published poems and prose by the handsome and dashing Colwyn Erasmus Arnold Philipps (1888-1915). Colwyn Philipps seems a kindred spirit to Captain, the Honorable Julian Henry Francis Grenfell, D.S.O., of the 1st BN Royal Dragoons. Both were cavalrymen. Both were born in 1888, and died in May, 1915. Both men met their fate at Ypres. And Philipps' short story "The Sniper," shares many similarities with Grenfell's own exploits at counter-sniping.

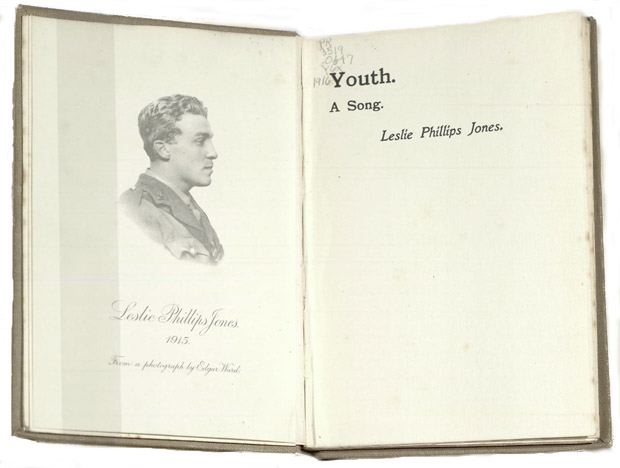

Youth : a Song / Leslie Phillips Jones. -- [Nottingham? : S.n., 1916]

A posthumously published collection of poems by Leslie Phillips Jones (1895-1915). Jones, a medical student before the war, sailed for the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli campaign, where he died of wounds on June 7th, 1915, just before his 20th birthday. (This was the battle to which Rupert Brooke was headed when he died en route.) Most of the poems in Jones' collection were written in the year just before the war, or in July 1914.

.jpg)

Pilgrimage : Poems / by Eric Shepherd. -- London ; New York : Longmans, Green, 1916.

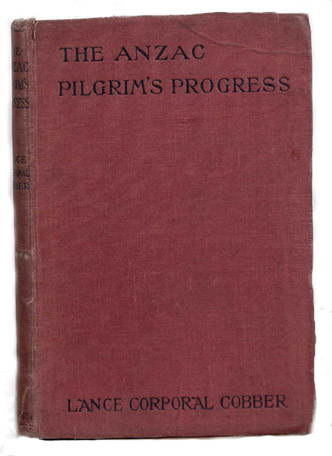

Poems by Eric Shepherd (1892- ), and another reminder of the influence of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress on the Great War generation (see also The Anzac Pilgrim's Progress : Ballads of Australia's Army by Lance-Corporal Cobber).

Soldier Songs / by Patrick MacGill, author of "Children of the Dead End." -- New York : E. P. Dutton & Co., 1917.

Collection of poems by Irish-born poet, Patrick MacGill (1890- ).

The experience of American poet Paul Green (1894-1981).

Poems by an American poet, Herbert Kaufman (1878- ).

Youth : and Other Poems / Robert Meader Easton. -- [England?] : Privately printed by his friends, 1931.

A posthumously published collection of poems by 22-year old Harvard student Robert Meader Easton (1908-1930). Easton was too young to be a soldier in the Great War, but apparently became an admirer of its icons: his poems include the overwrought urn "To Rupert Brooke" -- a piece of tortured meter and inordinate adoration guaranteed to keep Brooke hiding in his grave.

The Anzac Pilgrim's Progress : Ballads of Australia's Army / by Lance-Corporal Cobber ; edited by A. St. John Adcock. -- London : Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd., <1918>

The ANZACs (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) fought and bled much at Gallipoli in 1915 (the campaign to which Rupert Brooke was on his way when he died at sea). This volume reflects the unique, Poems / by Alexander G. Steven. -- Malvern, Victoria, Australia : <s.n., 1918?> Poems by Australian poet, Alexander G. (Alexander Gordon) Steven (1885-1923). self-effacing Australian outlook, at the same time that the title invokes the memory of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (see also Pilgrimage : Poems by Eric Shepherd). Preceding the poems there are also editorial explanations in mock-Bunyan/Coleridge-Rime of the Ancient Mariner style. There's every indication that the editor, A. St. John Adcock, is also the poet Lance-Corporal Cobber -- "cobber" being Aussie slang for friend, mate, companion, etc. -- the representative Australian enlisted man.

self-effacing Australian outlook, at the same time that the title invokes the memory of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (see also Pilgrimage : Poems by Eric Shepherd). Preceding the poems there are also editorial explanations in mock-Bunyan/Coleridge-Rime of the Ancient Mariner style. There's every indication that the editor, A. St. John Adcock, is also the poet Lance-Corporal Cobber -- "cobber" being Aussie slang for friend, mate, companion, etc. -- the representative Australian enlisted man.

If I Goes West / by a Tommy. -- London : George G. Harrap, 1918.

"To go West" is to die (see Siegfried Sassoon's "Memorial Tablet (GreatWar)" -- that is, to head in the opposite direction of the Continent and the Western Front, and towards good ol' "Blighty": England. To explain the author, "a Tommy," the story goes that at the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington once asked a dying British soldier his name, and the soldier replied "Thomas Atkins, sir." Coincidentally, in August 1815, the War Office issued the first "Soldier's Account Book," and its how-to-fill-out examples gave the hypothetical name "Thomas Atkins." Years later such popular works as Rudyard Kipling's poems "To Thomas Atkins," and "Tommy" helped to ensure that the nickname "Tommy" would forever be synonymous with the British private soldier -- at once, a generic term and term of endearment (as "G.I." would be to an American soldier). By taking the name "Tommy," the anonymous author of this collection has assumed the role of the representative British soldier. (For an Australian parallel, see The Anzac Pilgrim's Progress : Ballads of Australia's Army / by Lance-Corporal Cobber ; edited by A. St. John Adcock. And for more on "Trench" poetry and songs from the Great War, see the study in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/trench/.) The enlisted man's experience is rare, and this pseudonymous work adds ambiguity: was the author really enlisted? officer? or non-combatant?

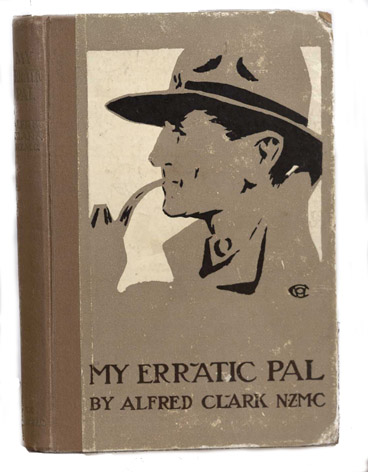

My Erratic Pal / by Alfred Clark. -- London, J. Lane, Bodley Head, 1918.

Poems by a member of the New Zealand Medical Corps.

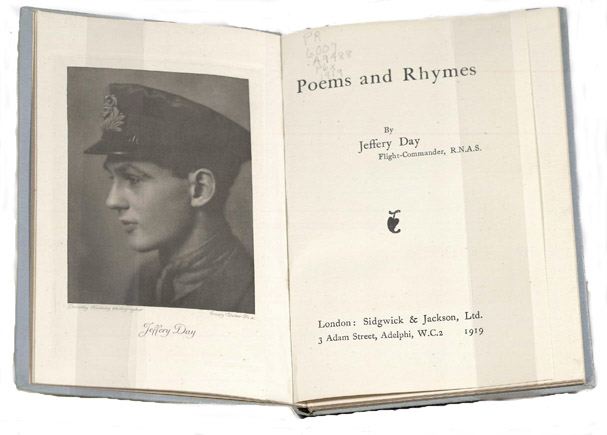

Jeffrey Day (1896-1918) was one of the very few flyer-poets -- and collections of poems by non-infantrymen are rare -- and one whose reputation has grown and is continuing to grow (see also Cambridge Poets 1914-1920: an Anthology which included Day in its collection).

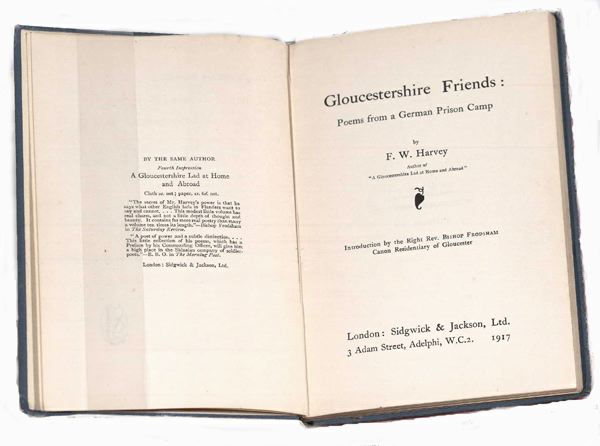

Gloucestershire Friends : Poems from a German Prison Camp / by F. W. Harvey, author of "A Gloucestershire Lad at Home and Abroad" ; Introduction by the Right Rev. Bishop Frodsham Canon Residentary of Gloucester. -- London : Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd., 1917.

The P.O.W. experience of F. W. (Frederick William) Harvey (1888-1957). It appears from the publication date (1917) that Harvey either escaped German captivity, or was allowed to send out his manuscript. Years later Harvey published a collection of his poems that included some of his early poems from the war: Gloucestershire : A Selection From the Poems of F.W. Harvey. -- 1st ed. -- Edinburgh : Oliver & Boyd, 1947.

Prisoners Grave and Gay / Lieut.-Colonel R. C. Bond. -- Edinburgh ; London : WM. Blackwood, 1934.

The P.O.W. experience was also told in prose by LTC Reginald Copleston Bond (1866- ), an officer in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (and author of The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the Great War, 1914-1918):

Battle and Beyond / by C. A. Renshaw. -- London : Erskine Macdonald, 1917.

A collection by C. A. (Constance Ada) Renshaw, and an example of the overlooked women's experience. (For more on Great War poetry written by women, see the study in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/women/, see also Catherine Reilly's anthology Scars Upon My Heart : Women's Poetry and Verse of the First World War).

So as through a glass and darkly

The age long strife I see

Where I fought in many guises,

Many names — but always me. General George S. Patton, Jr. (1885-1945)

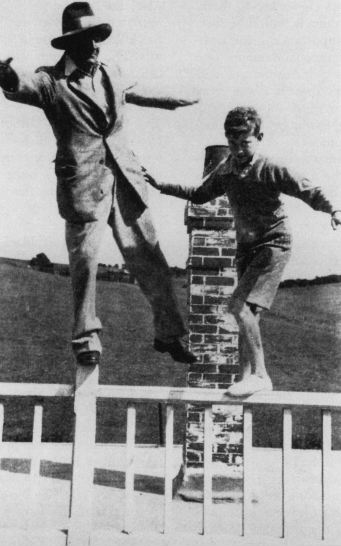

A. A. (Alan Alexander) Milne (1882-1956), famous for his stories about Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin, Tigger, Piglet and the rest, was a soldier in the Great War from 1915 to 1919 -- including the Battle of the Somme. Milne's poem "From a Full Heart" was included in The Sunny Side (1921), and prophesies his post-war retiring action from such woods as Delville, High, Mametz, and Trones, to Pooh's "The Hundred Acre Wood."

Saki (Hector Hugh Munro, 1870-1916), the great short-story writer of such masterpieces as "The Open Window," was killed on the 14th of November, 1916, while serving as a sergeant on the Western Front. Martin Stephen in his revealing Never Such Innocence: A New Anthology of Great War Verse (London : Buchan & Enright, 1988), has brought to light many heretofore overlooked Great War verses, among them Saki's wry "Carol."

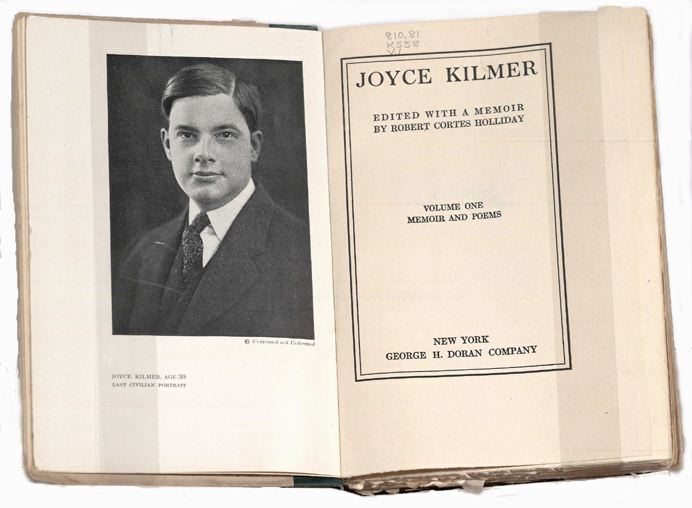

Joyce Kilmer, ed., with a memoir, by Robert Cortes Holliday. -- New York, George H. Doran company <c1918>

American poet, Joyce Kilmer (1886-1918), famous for the poem "Trees," was killed in France on July 30, 1918. Kilmer had bypassed a commission and risen in the ranks to sergeant (as had Saki) by the time he was killed. In his poem "Prayer of a Soldier in France," Kilmer's already deep religious faith (evident in much of his work) finds new understand from his perspective as an over-burdened soldier. Kilmer's "Rouge Bouquet" echoes Henry Timrod's "Ode" of the American Civil War: a fitting epitaph for a good (Christian) soldier such as Joyce Kilmer.

Another American poet might understandably be confused with the Joyce Kilmer of "Trees": that is, Edgar A. Guest, the author of "Home" ("It takes a heap o' living . . ."), and my favorite "The Auto." Guest (1881-1959) would have been a contemporary of the "older" (that is approaching and over 30) Great War poets: Brooke, Grenfell, Sassoon, Thomas, and Kilmer, for example. However, Guest chose to sit out the war, and instead offered moral(izing) support via a collection entitled

Over Here (1918), dedicated "To the Mothers Over Here," is a very instructive book: with such poem titles as "The Boy's Adventure," "The Complacent Slacker," "Do Your All," "The Flag on the Farm," "Fly a Clean Flag," "Life's Slacker," "Spring in the Trenches," "We Need a Few More Optimists," etc., etc., the collection provides an excellent example of the great gulf between the soldiers at the front and the civilians back home. Especially revealing is a comparision of Guest's poems "The Big Deeds," and "Hate" with Robert Graves' poems "Big Words," and "Hate Not, Fear Not." The perspective of the home-fire stoker, far across the sea, with that of the combat veteran.

In the Great War, George Smith Patton, Jr. (1885-1945) served as an officer in the fledgling American tank corps (they borrowed their tanks from the French), and was seriously wounded. Patton was a romantic (he was fond of quoting Rupert Brooke's sonnet "V. The Soldier" at the dinner table), who believed that through reincarnation he had soldiered through the centuries (as detailed in such poems as his "Mercenary's Song (A.D. 1600)," and "Through a Glass Darkly"). Patton was a competent versifier, and while everyone else in the world rejoiced at the end of the war (see Siegfried Sassoon's poem "Everyone Sang"), Patton, like a pacing Richard III, wrote his bitter "Peace -- November 11, 1918. However, the verdict is still out (according to Patton's biographer-grandson) on this interesting warrior-poet: "when Georgie was twenty he wrote a poem analyzing the thoughts of an ambitious young cadet. The poem, unfinished, began, 'His early mind perverted by untruthful literature/He sees a picture of war glorified/And knows not blood is pain and glory but a bubble.' It could be said, therefore, that Georgie spent his life trying to deny his youthful intuition that 'blood is pain and glory but a bubble'" (Patton, 283).