Stories of Battle

Literature of the Great War

The world before 1914 spoke a different, decidedly old–fashioned language. Edwardian Renaissance–men, like Rupert Brooke, wrote poetry for recreation. This earnest innocence was soon lost as the war revealed itself to be something quite the opposite of the expected chivalrous clash of arms on the field of honor. The challenge, then, for the generation of 1914 was how to rise to describe this so–called Great War, which was at once their defining moment and their worst nightmare.

Master craftsmen like Robert Graves and Wilfred Owen proved that poetry provided an unmatched immediacy for recording the bombardment and assault of experiences. But poetry, the genre of gentlemen, gave way to ironic memoir and gritty novel as the preferred form for others as they took more time to process the war (Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of a Fox–Hunting Man, and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet On The Western Front, respectively). Literature was then just one of the many casualties and victories of the war that changed everything, and continues to haunt us after a hundred years.

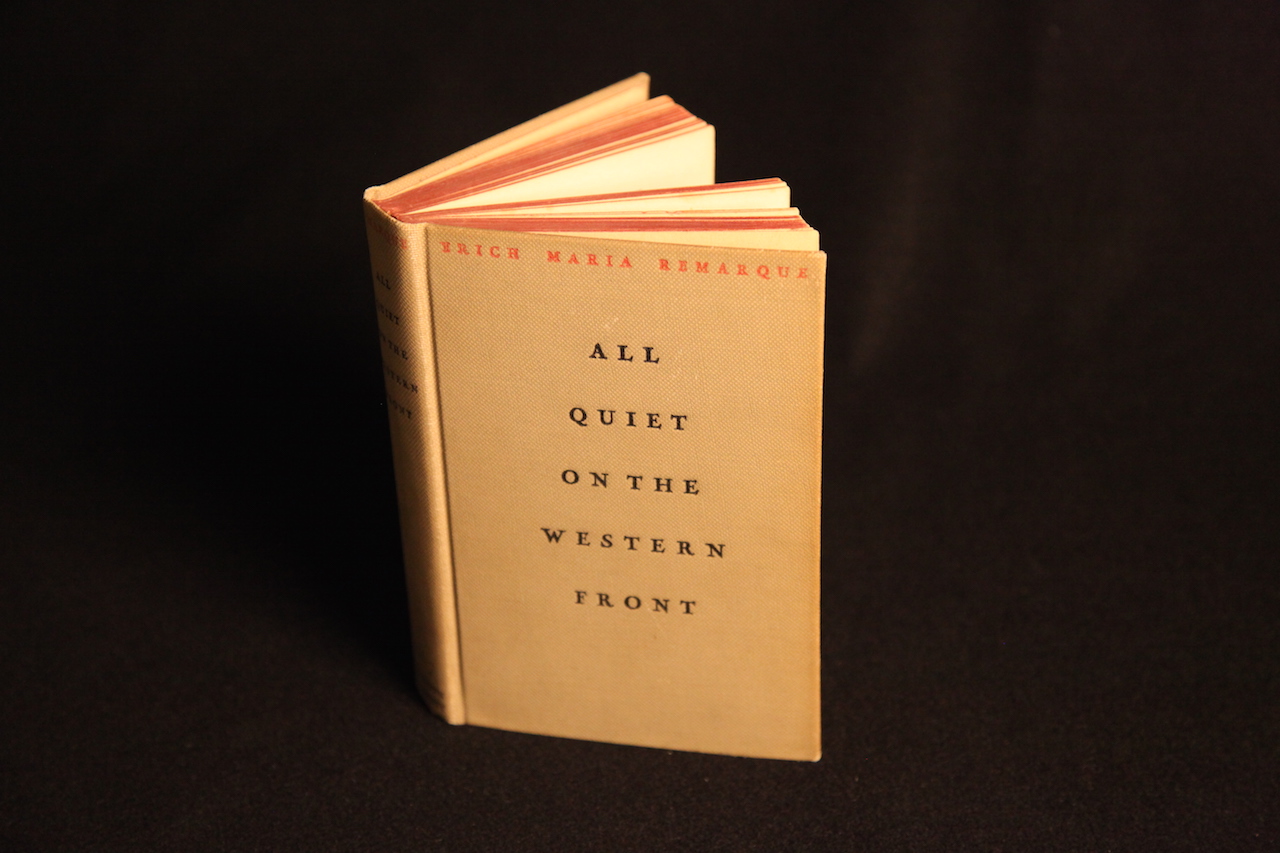

All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, translated from the German by A. W. Wheen

Erich Maria Remarque (1898–1970) was a German soldier in the Great War (although there is still some controversy as to just how much combat he experienced — and further controversy as to just how much difference that makes when considering his famous work of fiction). All Quiet on the Western Front is the English translation of Remarke’s Im Westen nichts Neues — one of the German classics of the war, and a book that Hitler (himself a gassed and decorated corporal in the Great War) hated, would like to have banned, and did have burned when he came to power for what he and the Nazi's saw as the book's portrayal of defeatism and weakness in the German Army during the Great War.

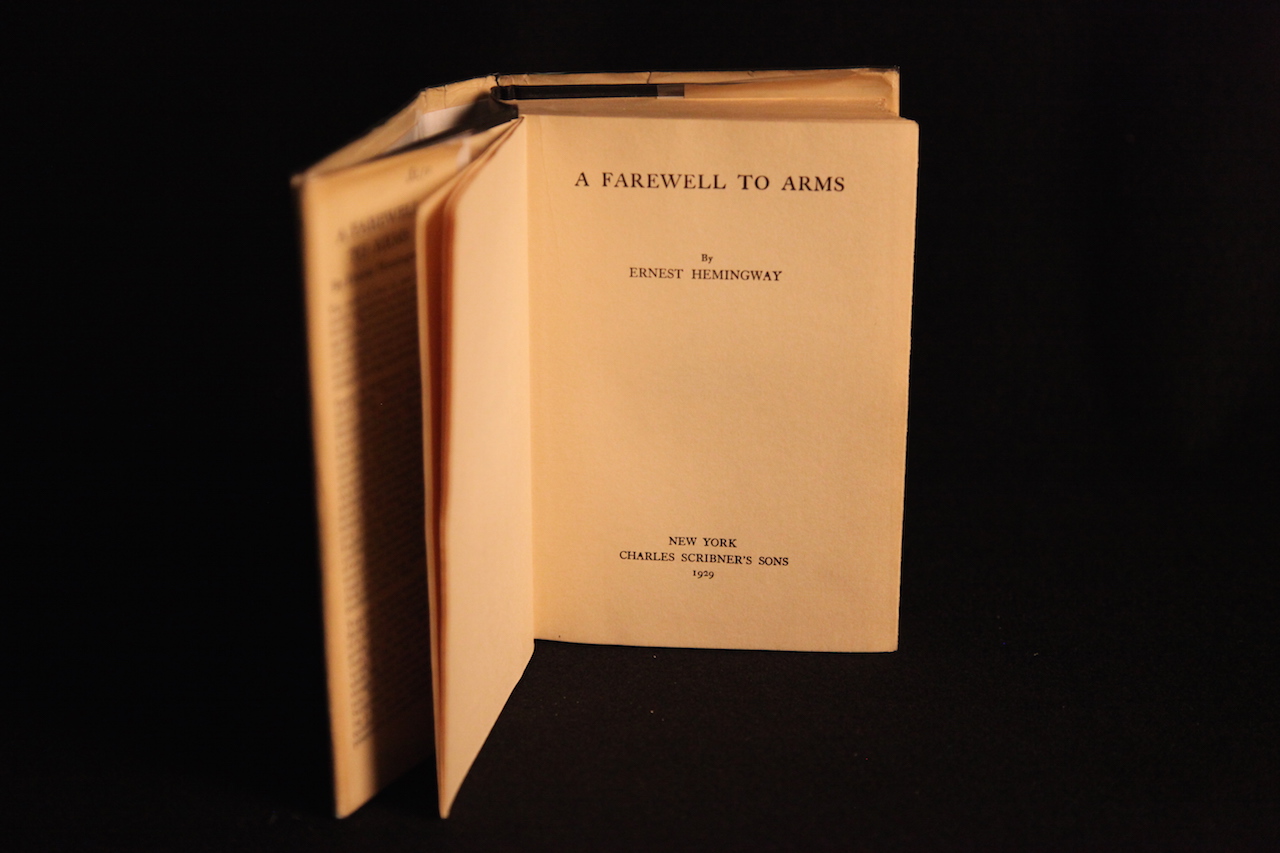

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

A Farewell to Arms is a tragic love story between Frederic Henry, an American fighting in the Italian Army, and Catherine Barkley, an English nurse. Its author, Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) was a volunteer ambulance driver in the Great War — along with other Americans such as John Dos Passos, Malcolm Cowley, Dashiell Hammatt, and E.E. Cummings. Walt Disney had finished stateside training to be an ambulance driver, and was on his way to France when the war ended.

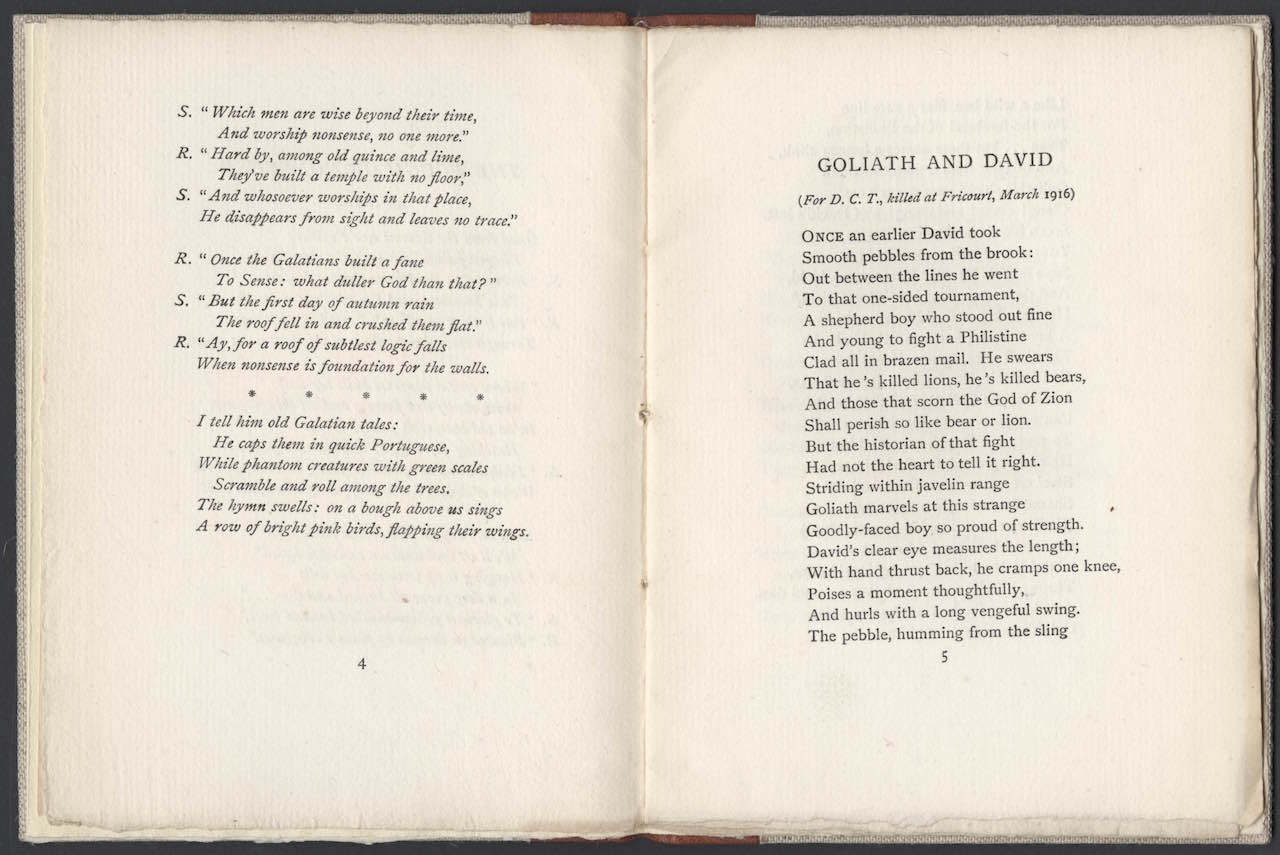

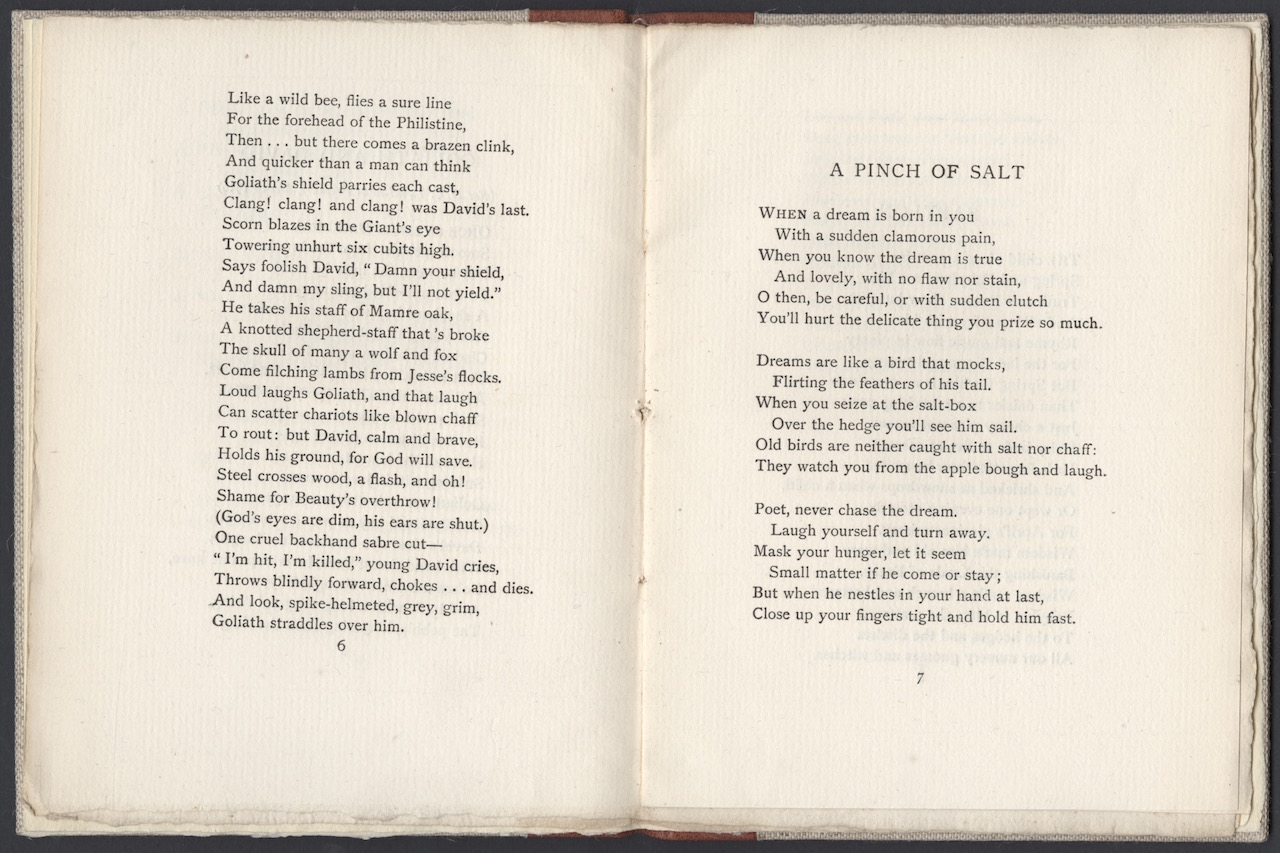

Goliath and David by Robert Graves

Robert Graves (1895–1985) is probably best remembered for his “autobiography” entitled Goodbye to All That (1929) which includes his Great War experience. The book earned enough money to provide Graves a happy self–exile in Majorca, Spain. Graves later excised much of his war poetry from his collected works, something which subsequent anthologists have respected. Today, Graves is also remembered by many as the author of a biography of T.E. Lawrence, the quasi–historical novel I Claudius, and his own poetical philosophy contained in The White Goddess.

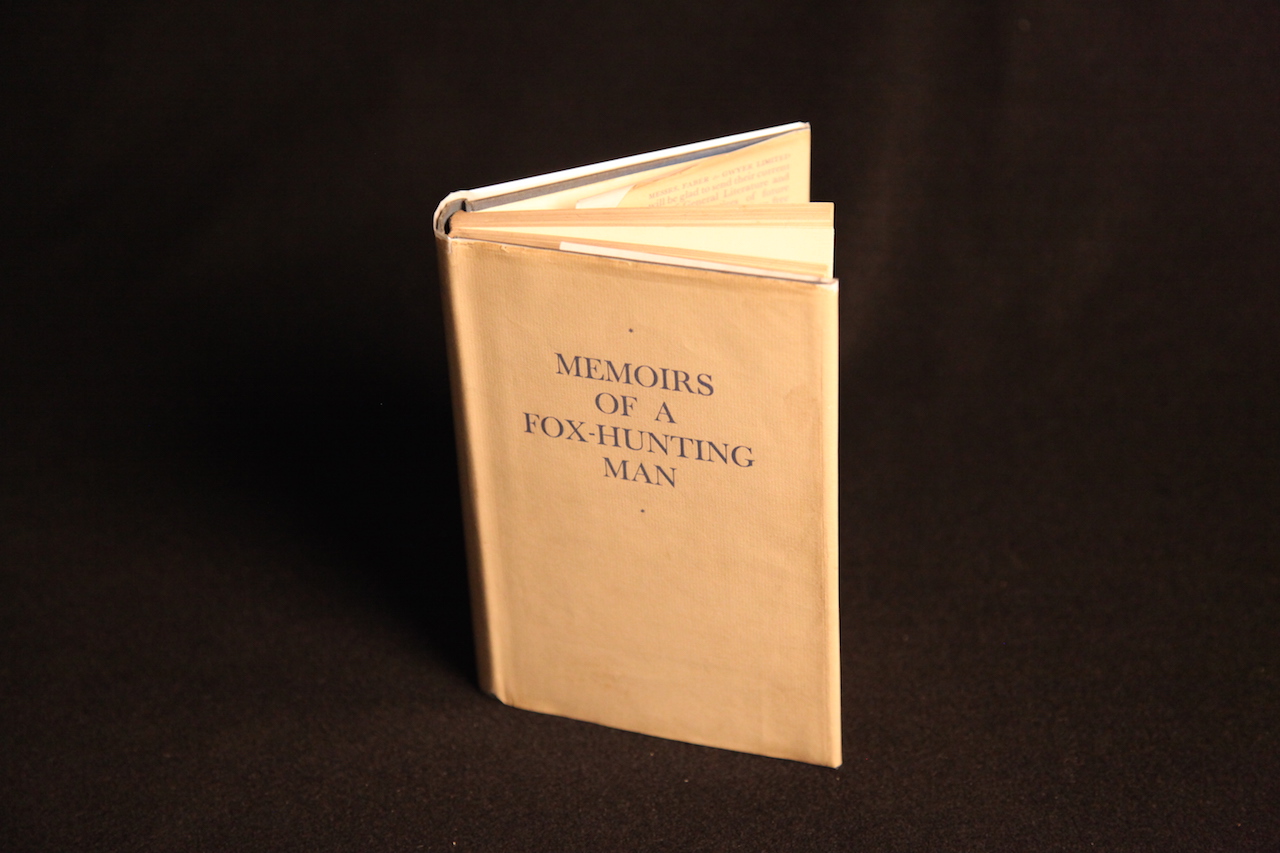

Memoirs of a Fox–Hunting Man by Siegfried Sassoon

One of the most famous Great War poets, Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) spent over twenty years reliving his life before, during, and after the Great War in six volumes of (barely fictionalized) memoir and (more straightforward) autobiography. Sassoon described himself as an “Enoch Arden,” compelled to revisit old haunts and walk over the ground again and again. In his first three volumes, collectively titled The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston (1937), Sassoon employed a fictional, less complicated version of himself to tell his story. Memoirs of a Fox–Hunting Man (1928) covers Sassoon’s (that is, George Sherston’s) privileged early life as a budding young country gentleman and fox–hunter, his enlistment in 1914, and return home on leave in 1916, before the Battle of the Somme. Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) continued the story of George Sherston in the war: the Battle of the Somme, getting wounded in 1917, being sent to “Slateford” (in reality, Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland). The final volume in the trilogy, Sherston’s Progress (1936) takes up the story at Craiglockhart Hospital, especially Sassoon’s/Sherston’s relationship with neurologist W.H.R. Rivers.