Gallery Guide

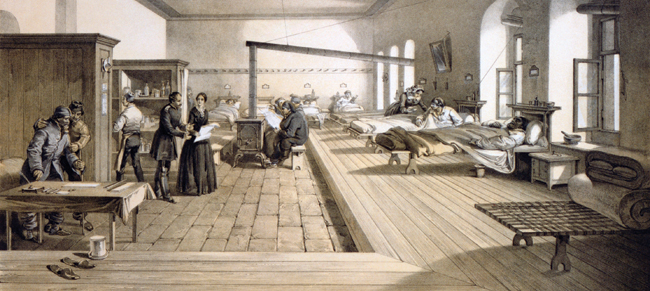

Lithograph of Nightingale at the Barracks Hospital in Scutari, 1856.

Her Life

Edward Cook, one of Florence Nightingale’s biographers, observed that “[t]he pioneers of one generation are forgotten when their work has passed into the accepted doctrine and practice of another.” 1 For many pioneering thinkers this may be the case; but for Florence Nightingale, whose path-breaking work on reforming sanitation and hospital care is legendary, nothing could be further from the truth. This year, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of her death, the Lee Library is pleased to join with BYU’s College of Nursing to sponsor this exhibition on the life and legacy of this health care pioneer.

Florence Nightingale was born in 1820 in Florence, Italy, while her parents, Frances Smith and William Edward Shore Nightingale, were enjoying an extended honeymoon. The Nightingales were members of England’s upper class and raised Florence and her older sister, Parthenope, on their two country estates in Derbyshire and Hampshire. During a time when girls were usually educated only in domestic skills, Nightingale received an extensive classical education from her father.

At age 16, Nightingale received the first of three calls to God’s service. She experienced a strong feeling that God had asked her to devote her life to His service. The Nightingale family expressed strong objections to Nightingale’s pursuit of nursing, which at the time was considered a menial job for lower-class women. They would have preferred that she assume the conventional role of Victorian, upper-class women by marrying well, bearing children, and becoming heavily engaged in social activities. Nightingale persisted, however. She was so convinced of her calling from God that she rejected two marriage proposals in order to devote herself entirely to His work.

Her formal training in nursing included three months at the Institution of Deaconesses at Kaiserwerth, Germany, where she learned current treatments and observed nursing administration. In 1853, at age 33, she was appointed superintendent at the Establishment for Gentlewomen during Illness in London. In this, her first position working directly with patients, Nightingale made many improvements to nursing care.

Title page of Notes on Nursing, 1st edition, 1859.

In 1854, Nightingale was appointed head of a contingent of nurses sent to care for soldiers involved in the Crimean War. She faced many challenges, including lack of food and supplies, resistance from some physicians, bureaucratic barriers, and unsanitary conditions. Nightingale worked long hours as she cared for ill and wounded soldiers, supervised nurses, obtained necessary supplies, wrote reports, and completed other administrative tasks. With help from a Sanitary Commission sent from England, Nightingale effected changes in hospital sanitation that significantly reduced soldiers’ mortality rates from illness. Reports of her dedicated work reached England, where she became a national hero. Based on these reports, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized Nightingale as the “lady with a lamp” in his poem “Santa Filomena.”

In 1856, Nightingale returned to England and took up permanent residence in London. She spent the rest of her life working to enact reform of army sanitation, hospitals, and a number of other public health efforts, including sanitation in the British colonies. Nightingale also made significant contributions to nursing education by founding the Nightingale School of Nursing in 1860. Most of her work after the Crimea was accomplished through meeting with politicians, gathering and sharing statistics, and writing reports and letters. In-person meetings were limited after 1857, however, when Nightingale declared herself an invalid because of the continuing effects from a fever she caught in the Crimea in 1855. She suffered chronic illness for the rest of her life. Her international renown, contributions in the Crimea, and subsequent health reform elevated nursing to a respectable profession. Nightingale died in 1910 at the age of 90.

Her Legacy

Nightingale’s work in improving sanitation, reforming health care, reducing mortality in army hospitals, and establishing a systematic method for teaching nurses was legendary, if not heroic. As the “lady with a lamp,” Nightingale’s image is fixed in our minds: a ministering angel of compassion, dedication, extraordinary intellect, and grit. A recent biographer commented on her legacy:

“We all know the romantic story of the wartime nurse. Comparatively few of us, though, are aware of the importance of that story’s sequel: of how, from her sickbed, Florence Nightingale, the possessor of one of the greatest analytical minds of her time, attempted to supervise the modernization of nursing, together with advising governments on Army health reform, sanitary improvements in Britain and India, hospital design, and much else besides.” 2

Nightingale — and her contributions — have been at times praised and panned. Her biographers would probably agree that, with all her complexity, she was a difficult subject to write about. That very complexity may be why she is of interest to many today. As the editors of her collected works have noted:

“Nightingale’s ideas might have more appeal now in the third millennium than in her own day. Certainly her more holistic approach to health care and emphasis on environmental factors and nutrition are popular now. Her highly positive conceptualization of human life will resonate with the present age, where it offended the dour hellfire and damnation adherents of her own.” 3

In addition to her pioneering work in sanitation and heath care, Nightingale’s quantitative research expanded the use of statistics. She developed the “polar-area diagram” to graphically display the causes of mortality in army hospitals, for example. Her efforts to gather, standardize, tabulate, and analyze data were ground breaking — and this in an age when these activities by women were frowned upon.

We owe much to the work of Florence Nightingale. The LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City — founded in 1905 — not only treated the sick, but also gave nurses the sort of education that Nightingale espoused. BYU’s College of Nursing continues this tradition of preparing nurses to serve society. And above all, the fact that most of us will live decades longer than our ancestors of a hundred years ago is evidence of her influence on health care. Indeed, we may say that our lives are her legacy.

Footnotes

1. Edward T. Cook, The Life of Florence Nightingale, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1913), 1: 417.

2. Mark Bostridge, Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), p. xxi–xxii.

3. Lynn McDonald, ed., Florence Nightingale: An Introduction to Her Life and Family, Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, vol. 1 (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001), p. 5.