More Bible Wars: The Reception of the King James Bible

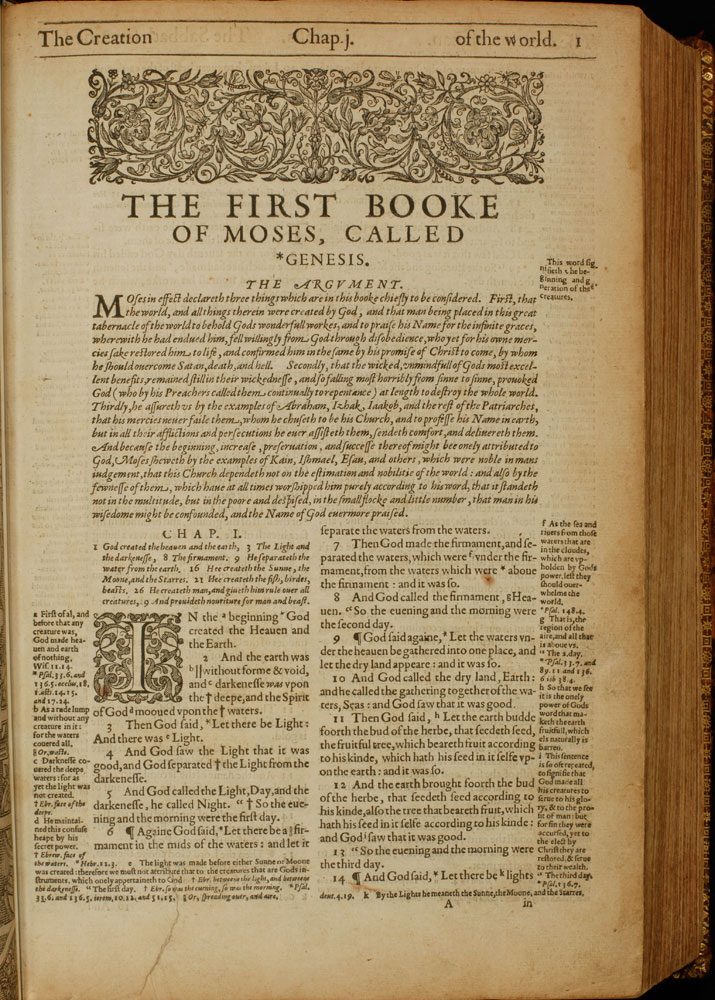

This folio-sized Bible was printed only a year after the King James Bible, by the same printer. The Geneva Bible was popular enough with readers that Robert Barker chose to continue printing it, even though he held a monopoly on printing the King James Version.

The King James Version did not gain overwhelming popularity for several decades after it first appeared. Many readers continued to use the preferred Geneva translation. As religious and political tensions soared during the reign of James's son, Charles I, the Geneva Bible came to be seen as the Bible of the Puritans and the King James Bible as the Bible of the Royalists. The Puritans, who believed Parliament should have more authority than the king, criticized the King James Version because it had been commissioned by a monarch rather than Parliament. Puritans also objected to the inclusion of the Apocrypha in the King James Bible and questioned the accuracy and style of the translation. However, during the Puritan Commonwealth (1649-60), the King James Bible remained in circulation.

With the restoration of the English monarchy, backlash against Puritanism labeled the Geneva Bible as seditious while the King James Bible was embraced as a symbol of religious and political unity. Over ensuing decades the King James Bible assumed its place as the definitive English translation of the holy scriptures.

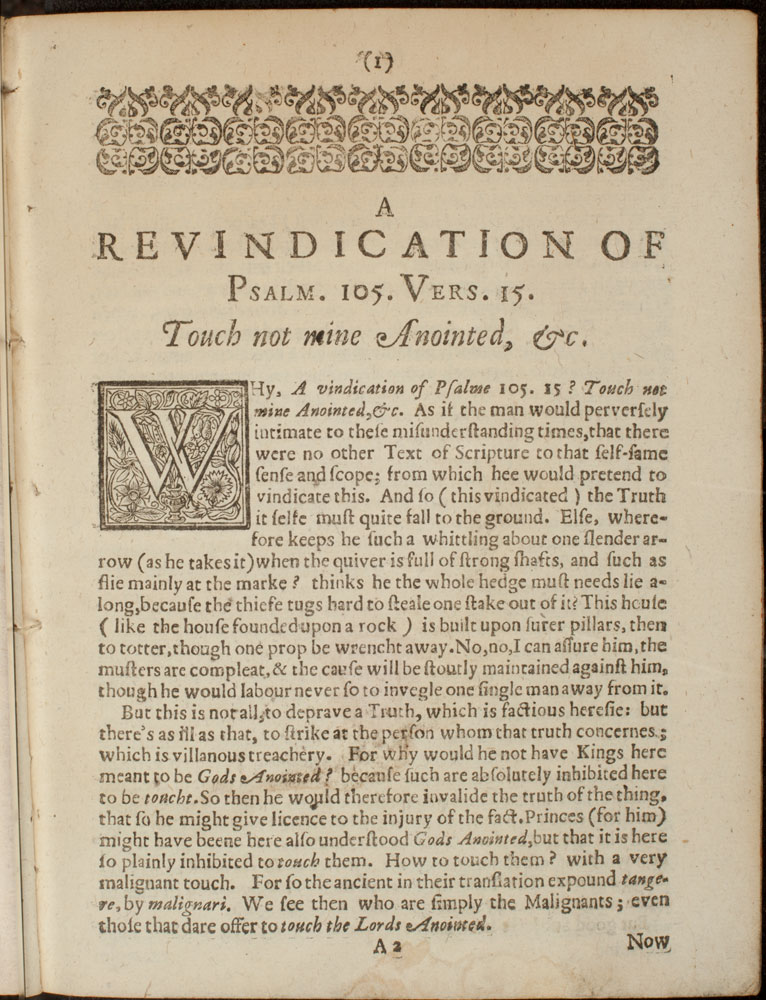

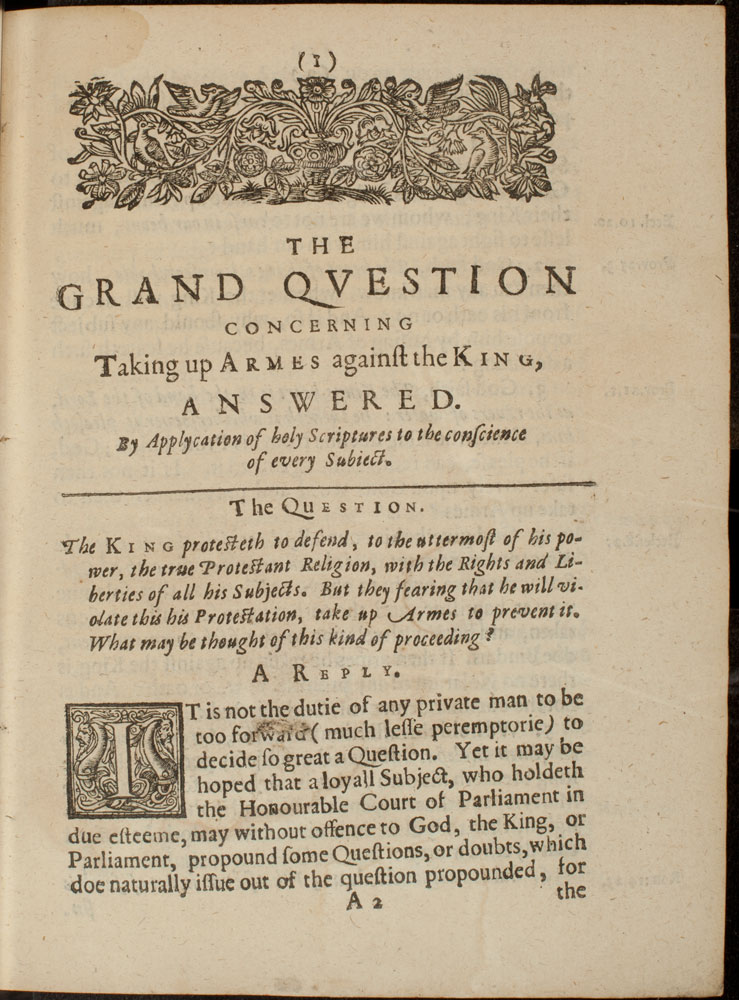

These anonymous pamphlets are representative of the many pro-Royalist tracts issued during the English Civil War. Many Royalist writers quoted the Bible, specifically the King James Version, to justify the cause of loyalty to Charles I. Parliamentarian writers, in contrast, rarely used scripture to argue their position.

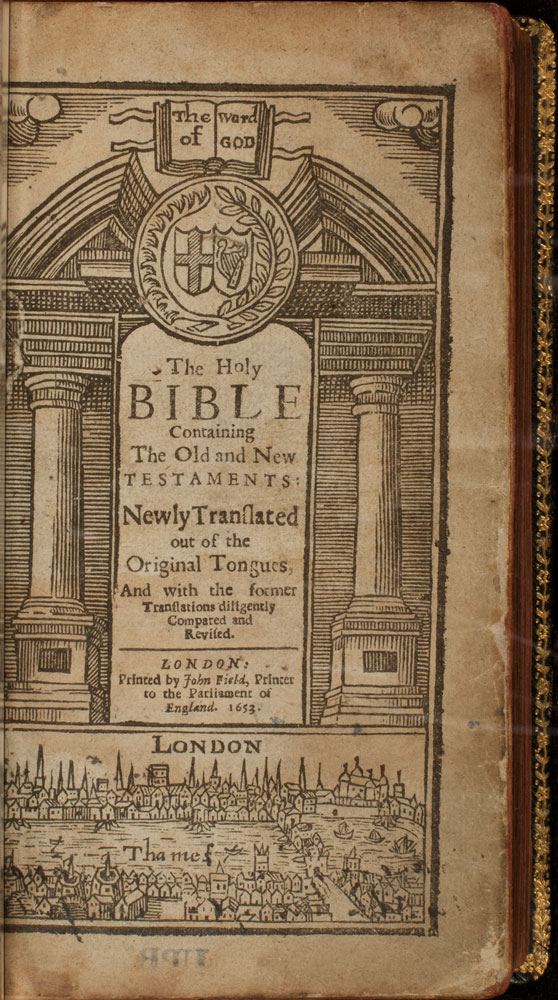

This edition of the King James Version was printed during the Commonwealth period. It is one of several editions from 1652 to 1653 that mention Parliament's authority on the title page. It does not contain the Apocrypha.