Transforming the World: The Impact of the King James Bible

The text of the King James Bible informed the voices of generations of English speakers. Along with the works of William Shakespeare, the King James Bible is cited as one of the greatest influences on the development of modern English. Publicly and privately, the King James Bible was read, heard, and studied by countless individuals in English-speaking countries and territories, and its language and style shaped their own thoughts and writings. Critics note the influence of the King James Bible—not just the stories, but the syntax and style—in works by many great orators and authors of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, especially in the United States.

The influence of the language of the King James Version is perhaps reduced today. The Bible is less central in modern culture, and there are many translations available to modern readers. Yet artists continue to be inspired by the language of the King James Bible, transforming it into a variety of works across many genres.

Handel composed the Messiah in the summer of 1741 based on a libretto compiled by Charles Jennens from the text of the King James Bible and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Handel premiered his work on April 13, 1742, in Dublin, Ireland. It is one of several of Handel's oratorios that take their text from the Bible. These pages are part of a small portion of the manuscript in Handel's own hand.

"Not Shakespeare nor Bacon, nor any great figure in English literature that one could name, has had so wide and deep an influence on the form and substance of all the literary and poetic work which followed during the next two centuries, as has the English Authorized Version of the Old and New Testaments."

—Laurence Housman, "The English Bible" (1937)

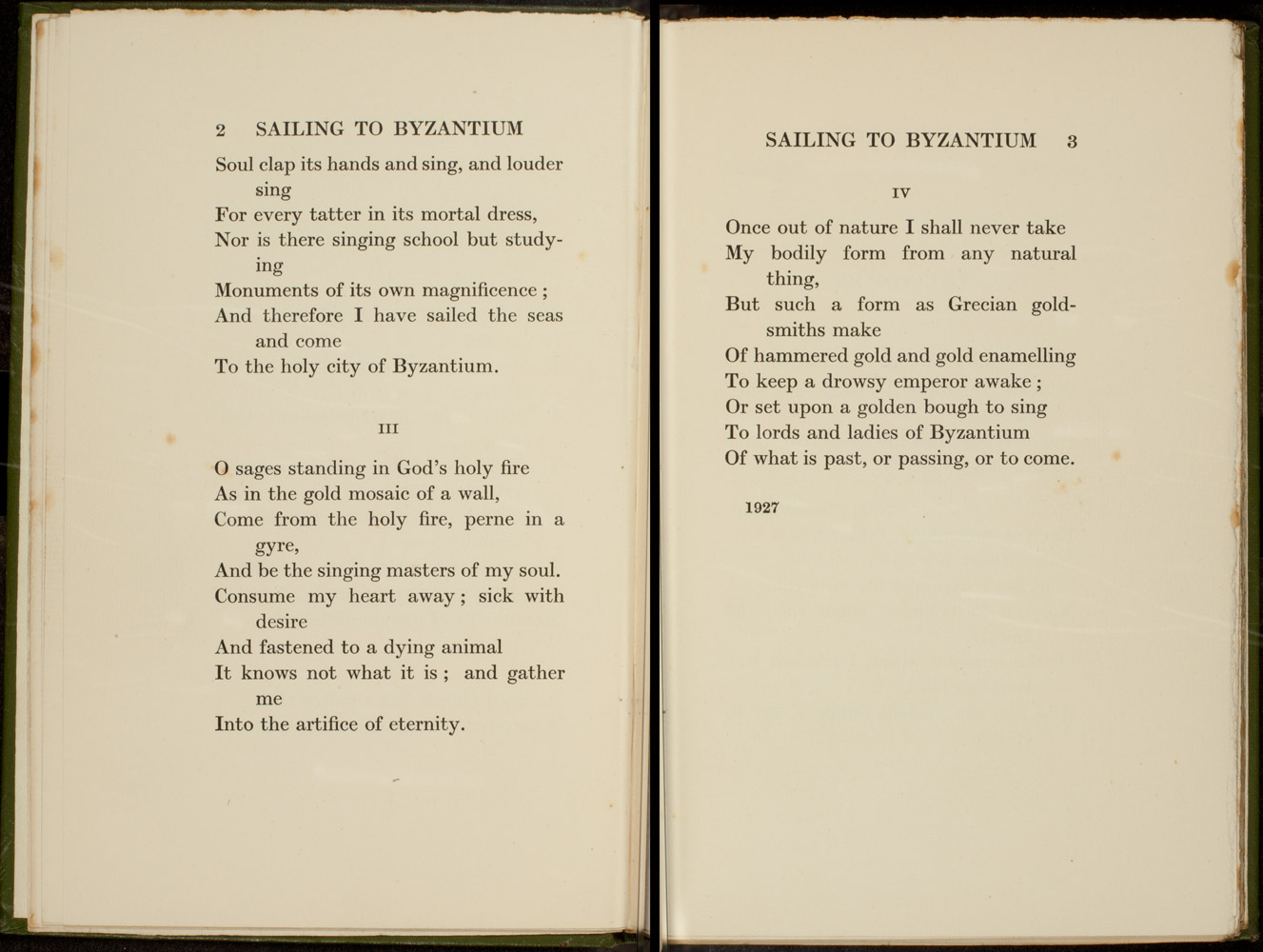

Yeats's use of phrases from the King James Version can be ironic and unorthodox. In "Sailing to Byzantium," Yeats evokes passages from Genesis, Daniel, the Psalms, New Testament epistles, and Revelations. The poem alludes to the story in Daniel 3, when Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego are thrown into a fiery furnace because they will not worship a golden image. Ironically, the speaker calls the sages out of the fire, but wishes to become the golden image itself, to be resurrected from "a natural body" (1 Cor. 15:44) into a graven image.

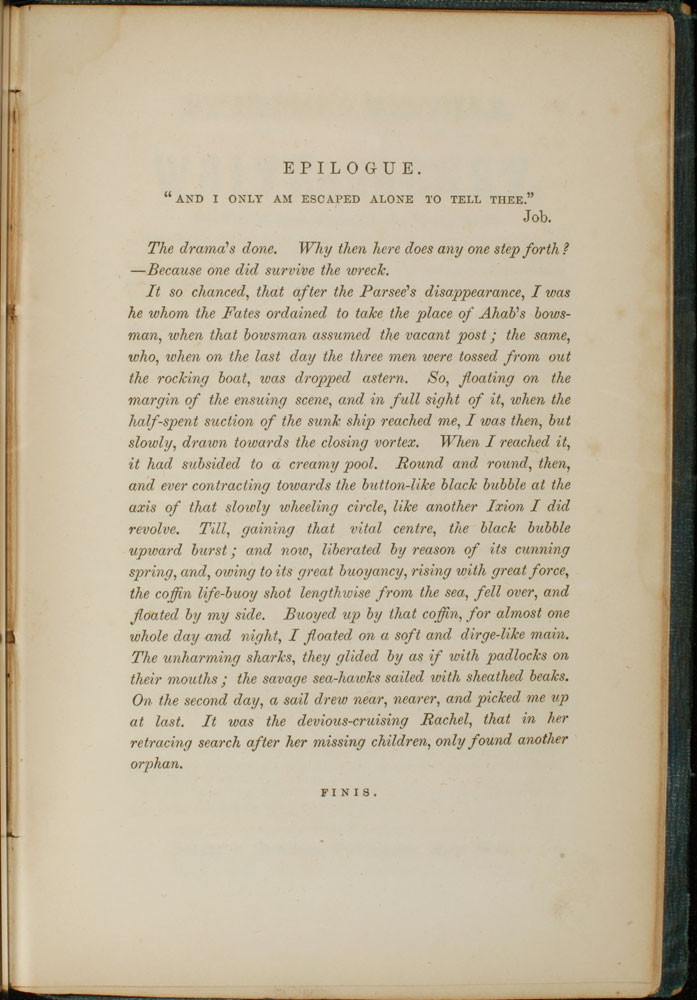

Melville's writings— even his journals and correspondence—show his familiarity with the stories and language of the King James Bible. The influence of the King James Version on Moby-Dick goes beyond allusions and quotations; Melville's imagery and idioms also imitate the language of the King James Version, and he often tries to adopt its structure. One critic calls Moby-Dick "a book of Biblical proportions," in that it is Melville's "homage to the Bible's own attempt to capture every shade of human experience and every imaginable mode of discourse."

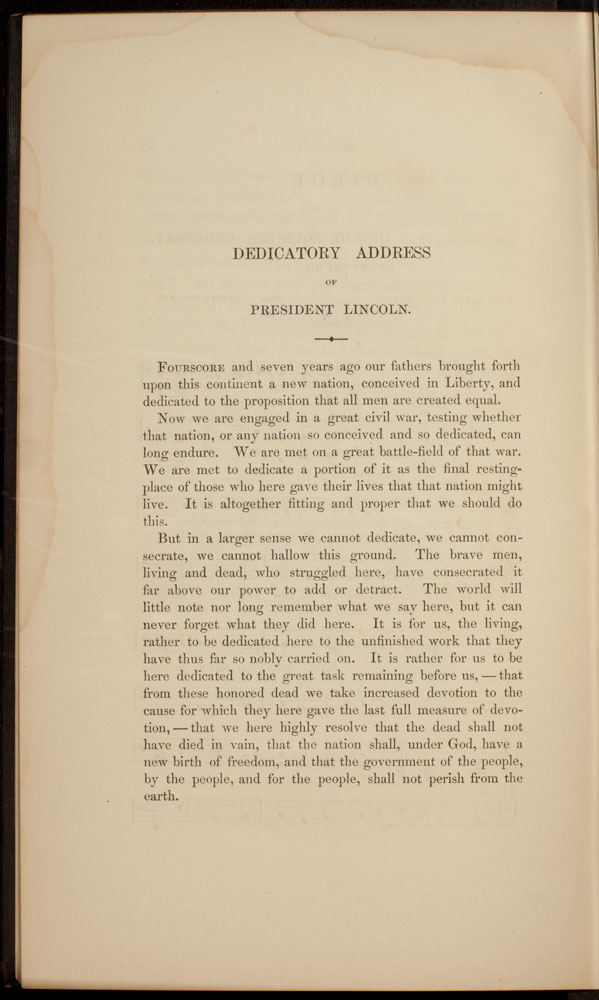

Lincoln was a frequent reader of the King James Bible and had been since childhood. He heard the text of the Bible at home, at church meetings, and even at school. He told the story of attending a "log schoolhouse in Indiana where . . . all our reading was done from the Bible. We stood in a long line and read in turn from it." Lincoln's speeches, including the Gettysburg Address, contain echoes of the King James Bible, and many critics believe that Lincoln's appropriation of biblical language is why his oratory is so stirring and vivid to audiences both today and in his own time.

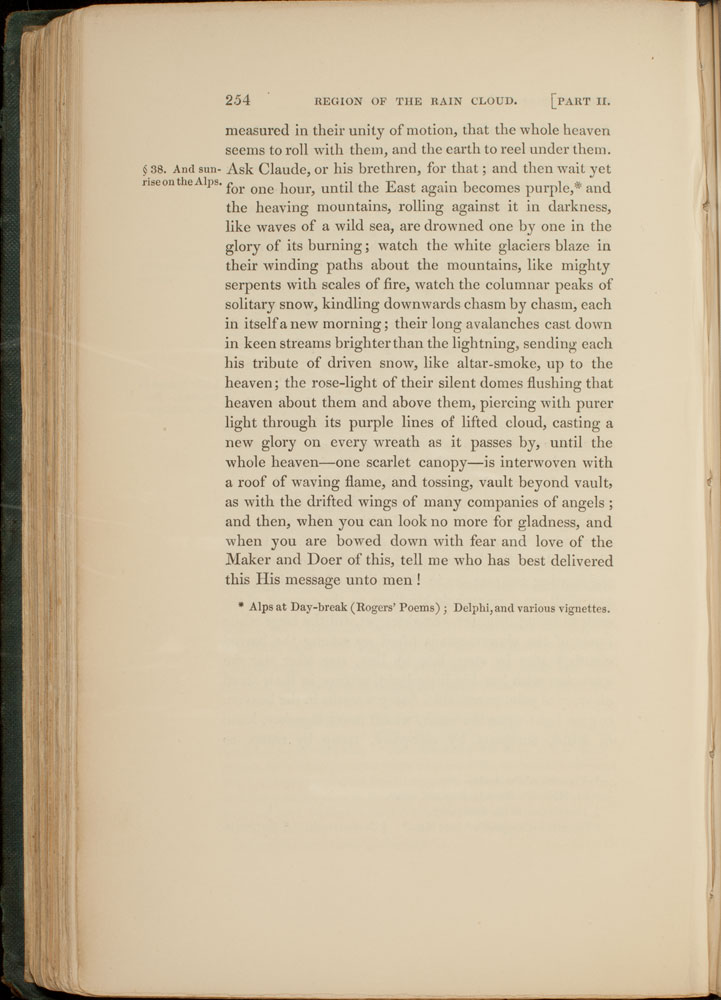

The eminent Victorian critic John Ruskin was deeply familiar with the King James Bible; he began reading it with his mother daily at the age of three. Ruskin's controversial first work of art criticism, Modern Painters, draws upon the rhetorical power of Biblical language to describe the works of English Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner.

"The King James Version of the Bible, once justifiably thought of as the national book of the American people, helped foster, at least for two centuries, a general responsiveness to the expressive, dignified use of language, to the ways in which the rhythms and diction of a certain kind of English could move readers."

—Robert Alter, Pen of Iron (2010)

The Grapes of Wrath contains numerous Biblical allusions, but Steinbeck specifically models the language of the King James Version in the interchapters of his novel. The syntax of these interchapters—the rhythm, the language, the use of repetition and contrast in the sentence structure—shows the distinct influence of the King James Bible's powerful prose. Steinbeck uses the interchapters to document the exodus of the Okies to the West Coast, just as the biblical book of Exodus recounts the Israelites' wanderings in the wilderness.