From Sketch to Print: Methods and Technologies

Scroll to seeauthors and artifacts

During the 19th century, printers constantly experimented with methods of reproducing illustrations, but three techniques were predominant: steel engraving, wood engraving, and lithography.

Steel engraving involves cutting a design into metal plate. The incised areas hold the ink which is transferred onto paper when it is run through a printing press. To print the illustration, sheets of paper would be pressed into the plate, soaking up the ink in the incised areas. Engraved steel plates were popular printing mediums in the 1830s and 1840s; many Charles Dickens novels were illustrated using this technique.

Later in the Victorian period, wood engraving became the preferred medium for graphic reproductions. To make a wood engraving, a craftsman would copy the original drawing onto the face of the end grain of a block of boxwood. An engraver would cut into the block with a v-shaped tool, excising the areas that would not be printed. Ink would be applied to the block, settling on the raised areas. This process, like steel engraving, allows for highly-detailed images with delicate lines, but wood engravings did not wear down as quickly as did steel. Wood engravings could be printed on conventional presses alongside moveable type, another advantage which advanced their popularity. Illustrations could also be photographically reproduced directly onto the wood and then cut into the block. This process was most common in the 1880s and 1890s.

In the first half of the 19th century, color images were usually printed in black and white and then colored by hand. Chromolithography began to be employed to print color images in the 1850s. An image would be drawn with a grease pencil or greasy ink onto a flat, porous surface such a stone or a metal plate. The image would be affixed to the plate with an acid bath. The plate would be coated with an ink mixture which adhered only to the greasy portion of the surface, sitting atop the flat surface of the printing plate. Typically, individual colors in the illustration would need their own plates. Wood engravings could also be used for color printing by cutting separate wood blocks for each individual color of ink. Each block would then be printed one after the other to create a single image.

Artifacts

H. K. Browne ("Phiz"). Original engraving plate from The Life and Adventures of David Copperfield: "Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my aunt."

The demand for Dickens' work was so high that his publishers had duplicate plates of each illustration engraved in order to keep up the pace of production. Individual plates are distinguishable by slight variations, such as changes in the signature of "Phiz," but it is impossible to tell which was made first. Printers Chapman & Hall retained many of the steel plates, but dispersed them in 1937

Charles Dickens. The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences & Observations of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849-1850

Many of Dickens' novels were issued in monthly parts, which contained several chapters of the book along with a few illustrations, stitched into paper covers. Each part cost one shilling, allowing readers to spread the cost of the book across many months. Shown here is part 12 of David Copperfield

Original engraved wood block from Harper's Weekly: "The Old Version" by T. Hovenden

This wood engraving block is comprised of four smaller blocks which were bolted together to form a large cover image for an issue of the American periodical Harper's Weekly. The block was formerly owned by Arthur w. Rushmore, a printer and designer who worked at Harper's.

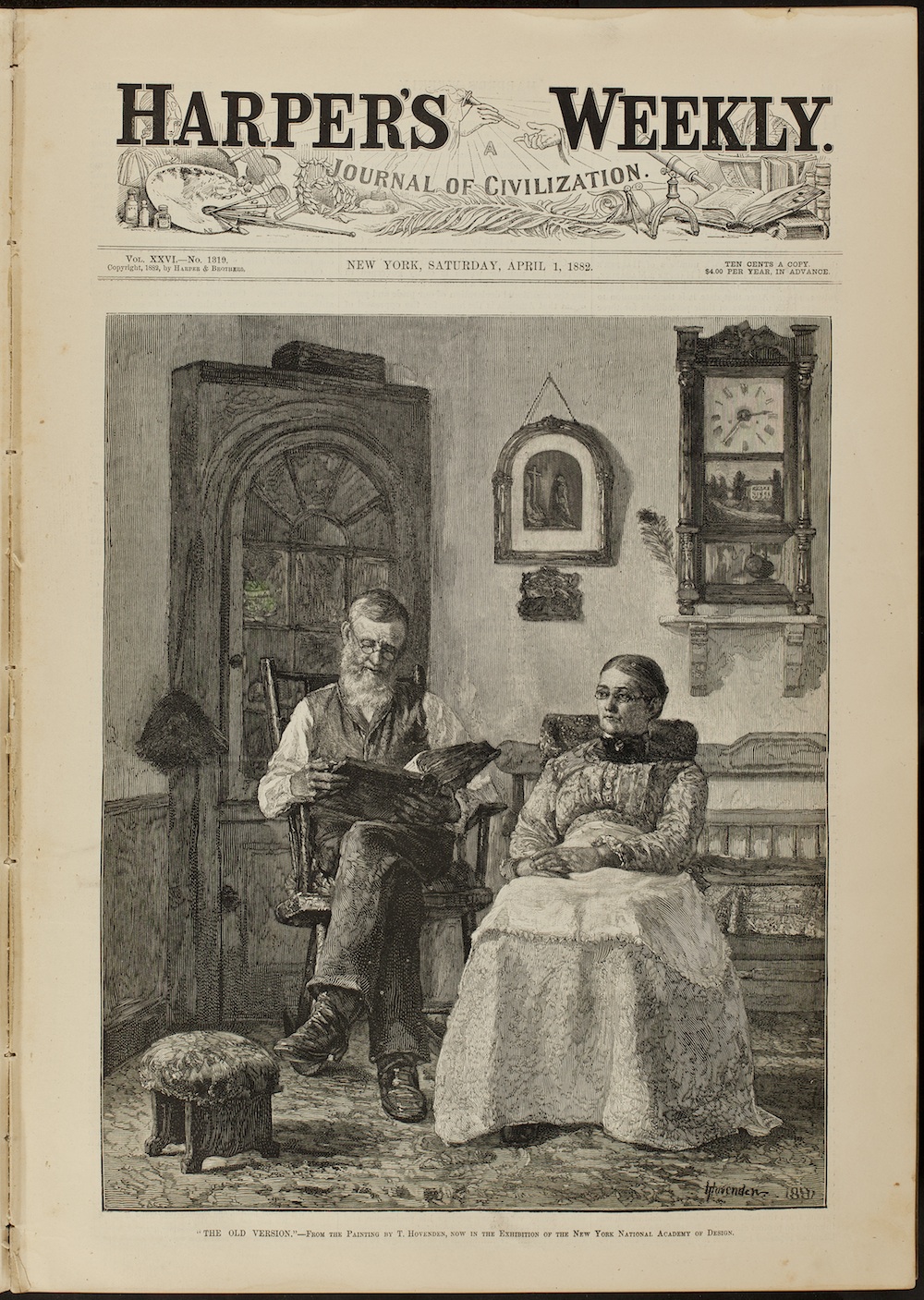

Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization Vol. 32 (April 1, 1882)

The cover image reproduces an 1881 painting by Irish-American artist Thomas Hovenden (1840-1895). It depicts a married couple on a Sunday afternoon; contemporary critics lauded the painting as a moral message about the sanctity of marriage and American domestic life at a time when divorce was becoming more common in American society.

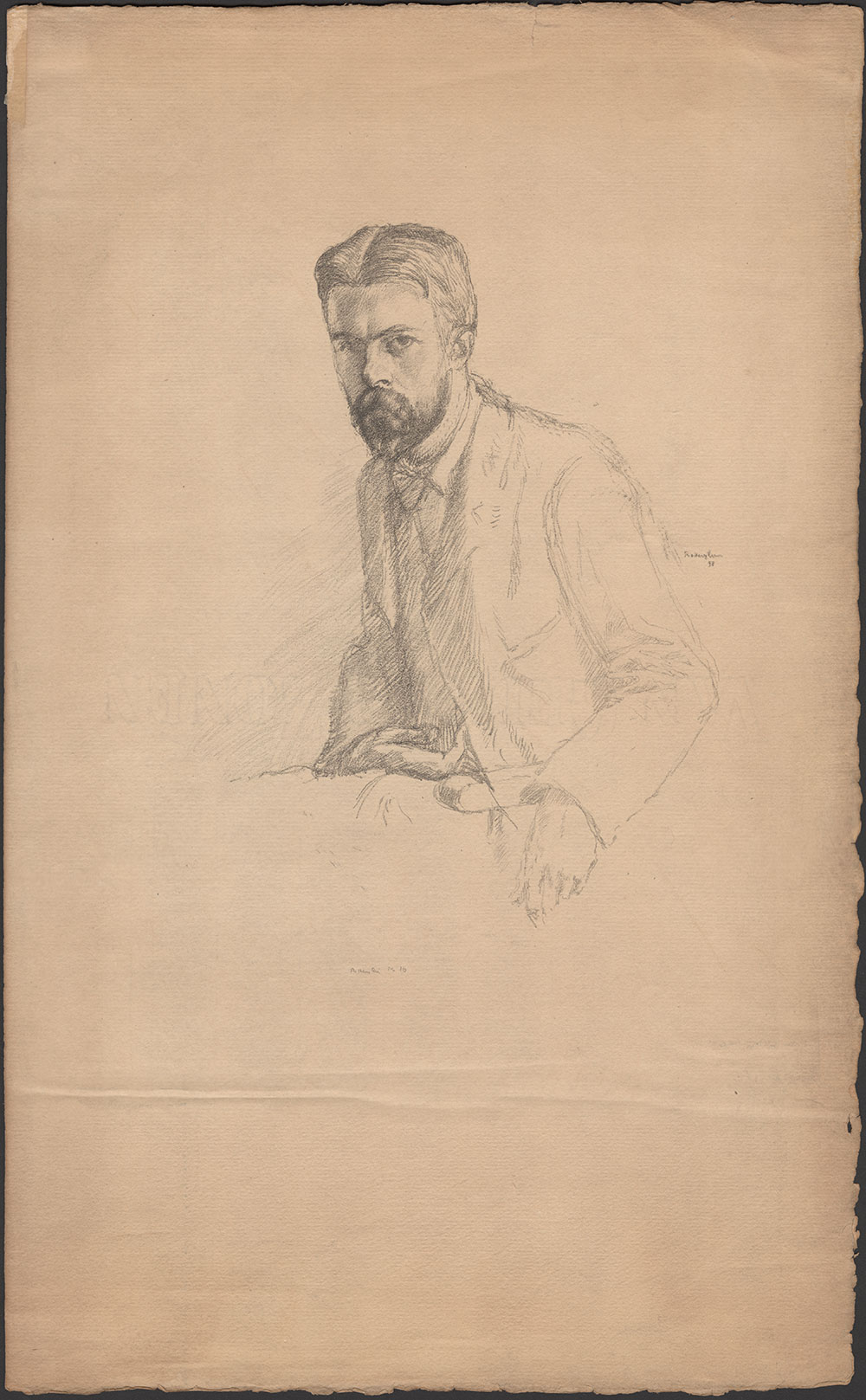

William Rothenstein. Proof lithograph portrait of Laurence Housman, 1898

English artist William Rothenstein (1872-1945) contributed illustrations to late Victorian magazines like The Yellow Book and The Savoy, but he is best known for his later portraiture and oil paintings. This lithograph has been retouched in pencil and signed by Rothenstein.