Effect on Families

Introduction

The Civil War was extremely difficult on the family unit. Typically, the father and eldest sons were the primary breadwinners, and families suffered great hardship when they left home to fight. After the war, 620,000 of these fathers and sons did not return. Thousands of those that did return home were wounded and maimed. As a result, many women found themselves widowed and alone, running farms, plantations, and businesses. Countless women spent the rest of their lives nursing the permanent physical and psychological wounds of their husbands and sons.

In hundreds of families, brother was indeed pitted against brother and father against son. The divided family was a reality and symbolic of a divided nation. Even husbands and wives were sometimes split in their loyalties. The effects of the Civil War on the family were long-lasting and permeated many aspects of everyday family life for generations after the fighting stopped.

Kane Correspondence

Thomas Leiper Kane, 1822-1883, was a lawyer, soldier, philanthropist, entrepreneur, and defender of the Mormons. In 1846, when he read of the forced exodus of the Mormon people from Nauvoo, Illinois, Thomas L. Kane sought help for them from the U.S. government and journeyed to the Mormon settlements to offer his assistance to Brigham Young. He became Brigham Young’s closest non-Mormon friend. Thomas L. Kane’s communication skills, integrity, and compassion for the Mormon people were effective tools in defending the Latter-day Saints throughout his lifetime.

Kane married his second cousin, Elizabeth Dennistoun Wood, 1836-1909, on 21 April, 1853. Notwithstanding her youth, Elizabeth was a woman of outstanding intellectual abilities and compassion. She was a photographer, an author, and a doctor.

In April 1861, Thomas L. Kane was the first Pennsylvanian to enlist for service in the Civil War. He was commissioned by President Abraham Lincoln to organize a volunteer regiment for the Union Army. This rifle regiment was known as the “Bucktails”. He was first commissioned as a Lieutenant Colonel and was later promoted to the rank of General.

In the Thomas L. and Elizabeth W. Kane Collection, there are approximately 800 letters between Elizabeth and Thomas penned during the Civil War period. A select few of them are here exhibited.

View 4 images

View 4 images

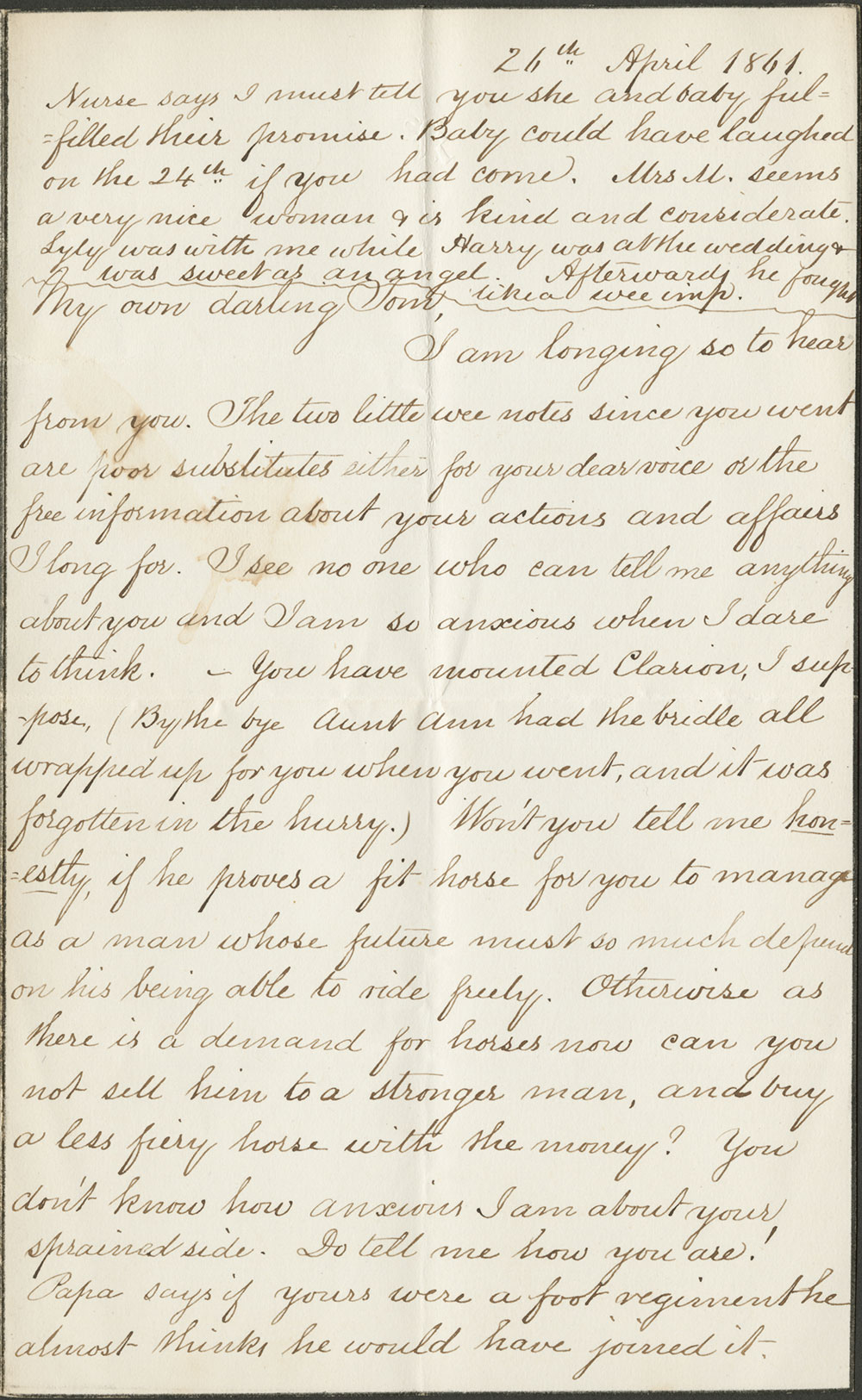

Elizabeth Kane to Thomas L. Kane 26 April, 1861 (Vault MSS 792, Box 21, Folder 1, Item 3)

My own darling Tom:

I am longing so to hear from you. The two little wee notes since you went are poor substi- tutes either for your dear voice or the free information about your actions and affairs I long for. ..... Do not be uneasy about me, my dearest ....I am not going to be the last straw to break your back.

May He who blessed your work in Utah send his reward in sparing you from the fearful necessity of fighting; I feel as if I could not stop saying God bless you again & again.

View 8 images

View 8 images

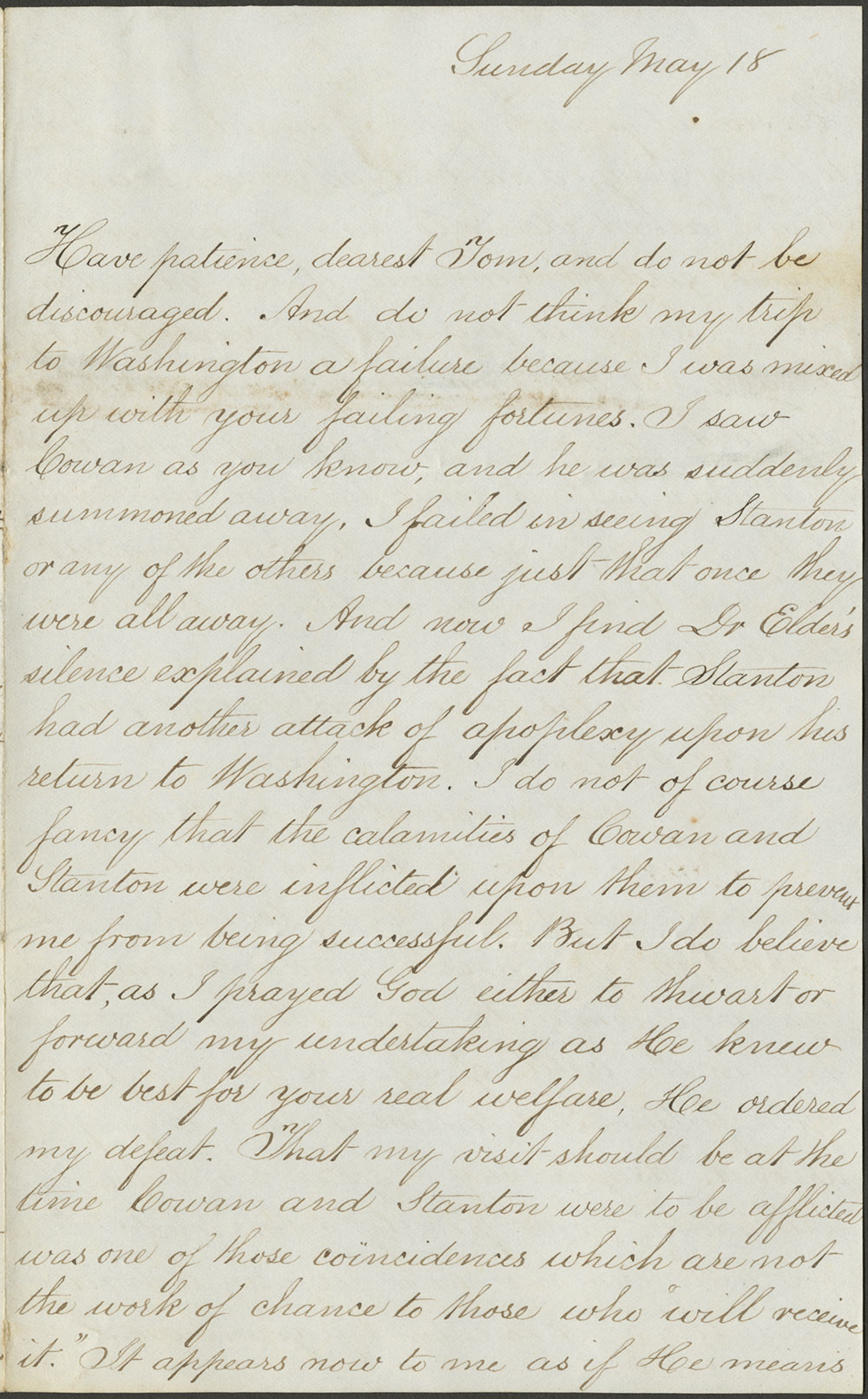

Elizabeth Kane to Thomas L. Kane. 18 May, 1862 (Vault MSS 792, Box 21, Folder 2, Item 80)

I trust that the Supreme Governor will soon bring our troubles to an end, and that He will find us somewhat purified. In the disavowal of Hunter’s Proclamation* the troubles that are to come towards the close of the war will begin. The North will be divided upon this question. As Joe Smith’s prophecy approaches fulfill- ment, I wonder what the Saints are hatching in the way of treason! --- And if there should be a split in the country I wonder which side the army will take.

*On 9 May, 1862, General David Hunter, without permission from President Lincoln, declared the emancipation of all slaves living within his Department (Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina). On 19 May, President Lincoln declared Hunter’s Proclamation altogether void, because the General, he said, did not have the authority to make such a proclamation. It is obvious from Elizabeth’s letter that both Elizabeth and Thomas Kane disagreed with the President.

View 6 images

View 6 images

Elizabeth Kane to Thomas L. Kane. 21 June, 1861 (Vault MSS 792, Box 21, Folder 1, Item 29)

I pray Him to give you strength of body, prudence, foresight and perseverance, hope and faith. May He help you to do your duty, day by day, and if you go into battle to go cherishing no animosity in your heart towards any living soul. It may be for your further trial that you should be opposed to General Johnston. [Albert Sidney Johnston was the General who led his army to Utah in 1857 in what has come to be known as the Utah War. He was the highest ranking Confederate officer killed during the Civil War.] I don’t know whether he has wronged you or the Mormons, but I pray you, dear one, to forgive him for the dear sake of Him who forgave with the crown of thorns round his temples.

View 4 images

View 4 images

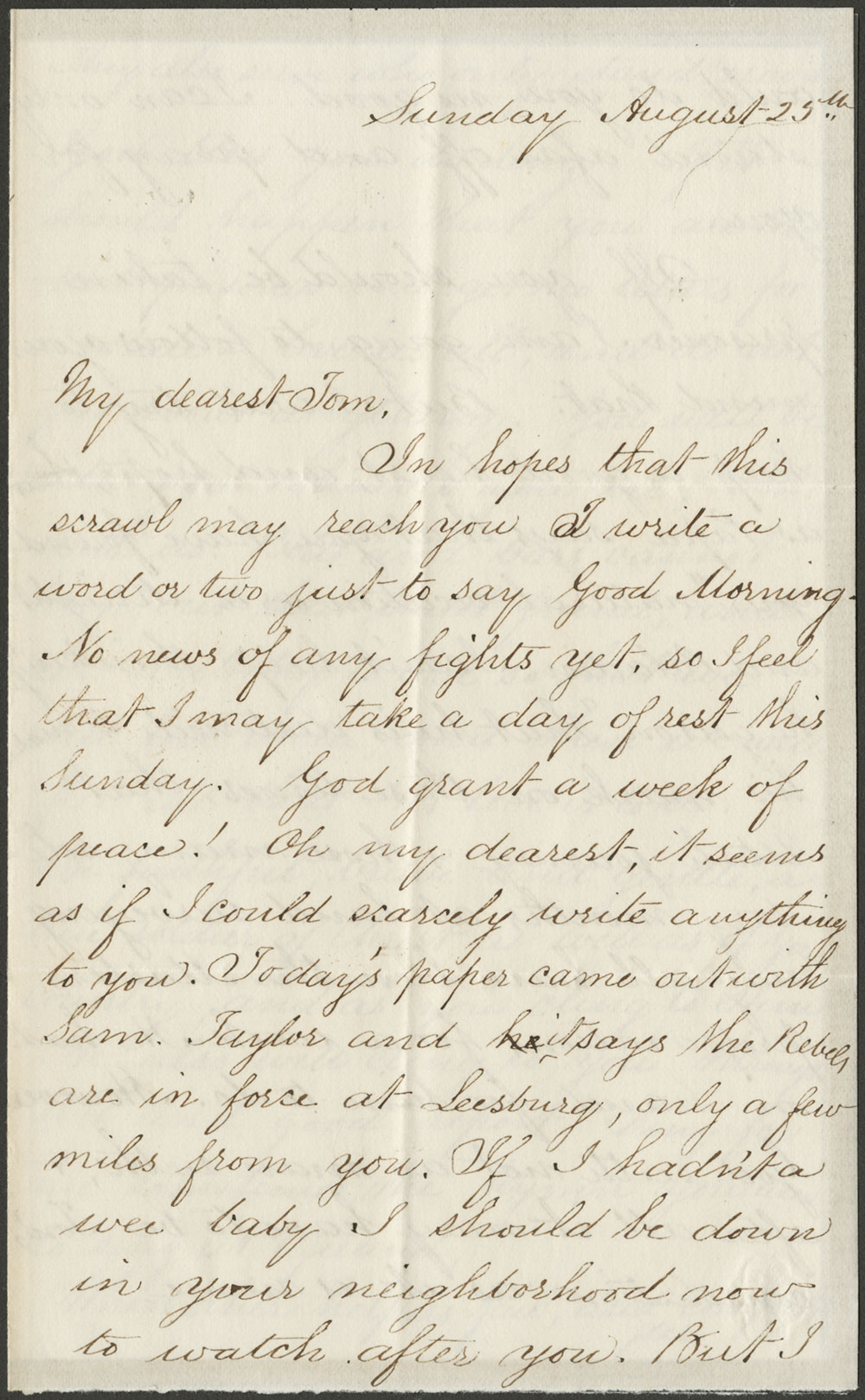

Elizabeth Kane to Thomas L. Kane. 25 August, 1861 (Vault MSS 792, Box 21, Folder 1, Item 52)

If you should be taken prisoner I am going to follow you, mind that. But I will try to keep a good heart, and hope, as Papa says, that you have found your “natural vocation as a Knight and Paladin. I can’t help thinking," he goes on, "that he is destined to make his mark on these times, that Utah journey & those many solitary months at land surveying may all have been the Master's preparations for a work He had on hand for him to do."

Explanatory text for the next five letters

Appointed Brigadier-General for gallant services on 7 September 1862, Thomas L. Kane commanded the Second Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Army Corps at the Battle of Chancellorsville, from 30 April to 6 May, 1863. Suffering from pneumonia shortly thereafter, he was in a Baltimore hospital when he heard of the Confederate armies marching into his home state of Pennsylvania. He left his sick bed, traveled to Gettysburg all night, and assumed command of his Brigade at 6:00 a.m. on the morning of 2 July. He wrote the following letters and reports just days after the battle.

View 1 image

View 1 image

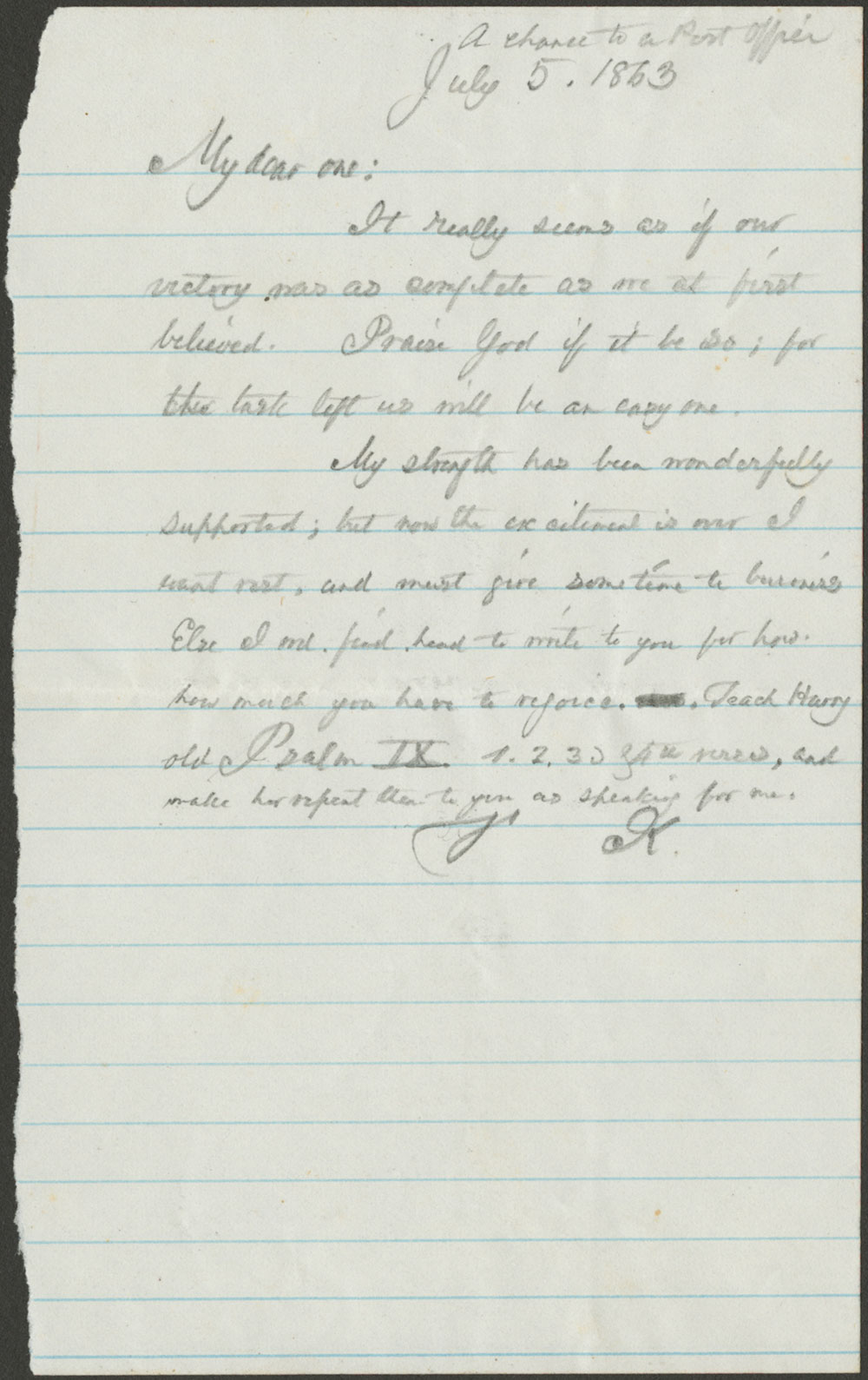

Thomas L. Kane to Elizabeth Kane. 5 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 22, Folder 2, Item 78)

My dear one:

It really seems as if our victory was as complete as we at first believed. Praise God if it be so, for the task left us will be an easy one. My strength has been wonderfully supported, but now the excitement is over I want rest...

View 4 images

View 4 images

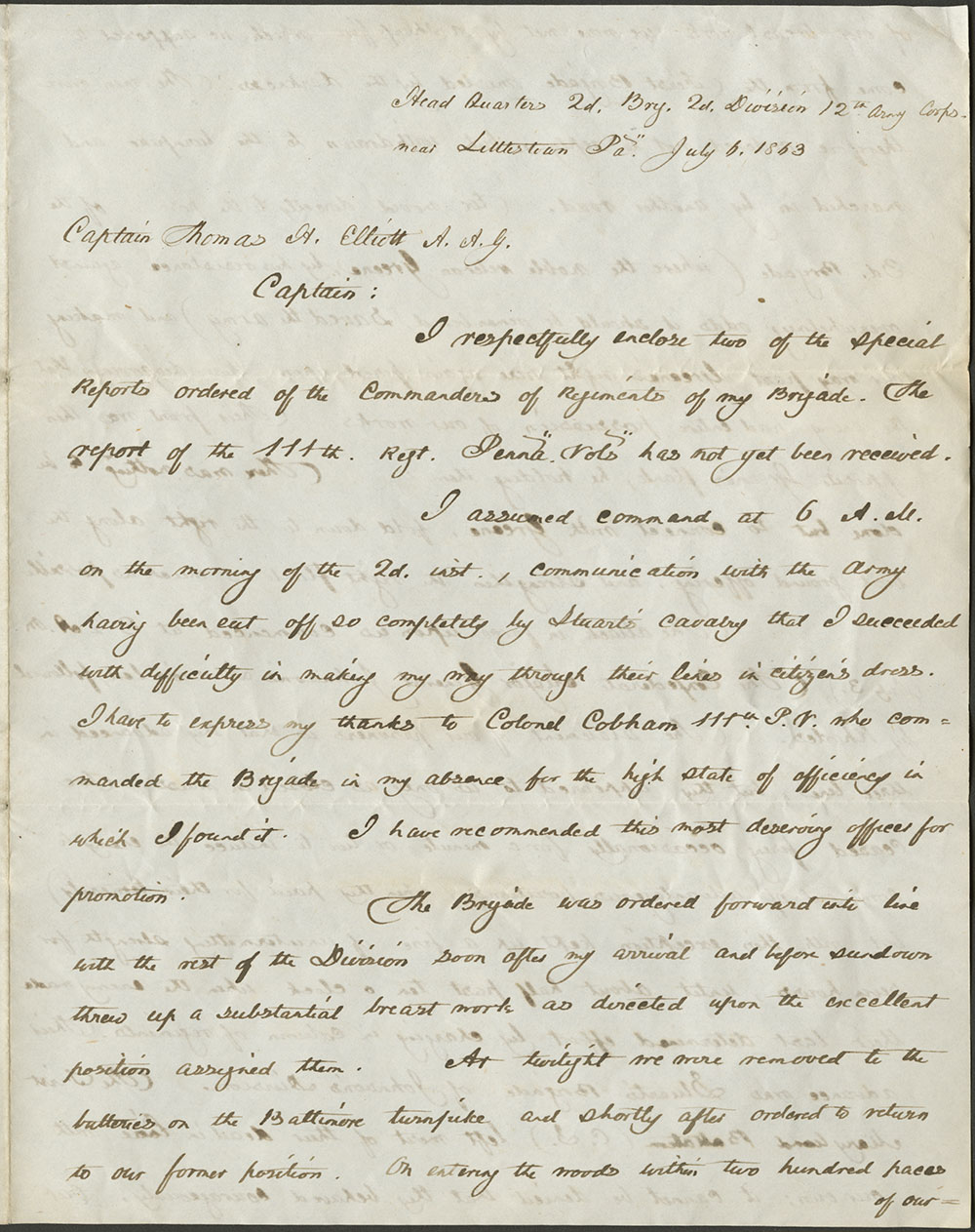

General Thomas L. Kane to Captain Thomas H. Elliott 6 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 23, Folder 6, Item 29)

[Official report of his regiment’s involvement in the Battle of Gettysburg composed by General Thomas L. Kane and written in his own hand]

I assumed command at 6 A.M. on the morning of the 2d., communication with the army having been cut off so completely by Stuarts’ cavalry that I succeeded with difficulty in making my way through their lines in citizen’s dress .... The attack in force upon us commended at 3 1⁄2 A.M. (July 3) ...we kept up a fire of unintermitting strength for seven hours, until about half past ten o’clock when the enemy made their last determined effort by charging in column of regiments. Their advance was Stuart’s Brigade ....Our own loss was but 23 killed and 73 wounded.

After this repulse the enemy fell back, and although they kept up a desultory fire for some time afterwards, it was plain, as the result proved, that the battle was over ... I have not the names of a single straggler or recreant reported to me. Every officer and man of my command did his duty ...

![General Thomas L. Kane to Lt. Col. H.C. Rodgers [with a forwarding recommendation from J.L. Dunn]. 6 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 23, Folder 6, Item 31)](http://files.lib.byu.edu/exhibits/civilwar/families/kane_rodgers_july_6_1863_1.jpg) View 3 images

View 3 images

General Thomas L. Kane to Lt. Col. H.C. Rodgers [with a forwarding recommendation from J.L. Dunn]. 6 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 23, Folder 6, Item 31)

Colonel:

I respectfully apply for leave of absence grounded on the accompanying certificate. [He had left the hospital in Baltimore, sick with pneumonia, to join his brigade at Gettysburg.]

Brg. Gen. Thomas L. Kane Commanding 2d. Brg. 2d. Division 12th A.C. having applied for a certificate on which to ground a leave of absence, I do hereby certify that I have carefully examined this officer and find him suffering from general debility following a severe attack of pleuritis also increased by exposure during the late Battle of Gettysburg in which he took an active part, although physically unfit for duty at the time. J.L. Dunn

View 1 image

View 1 image

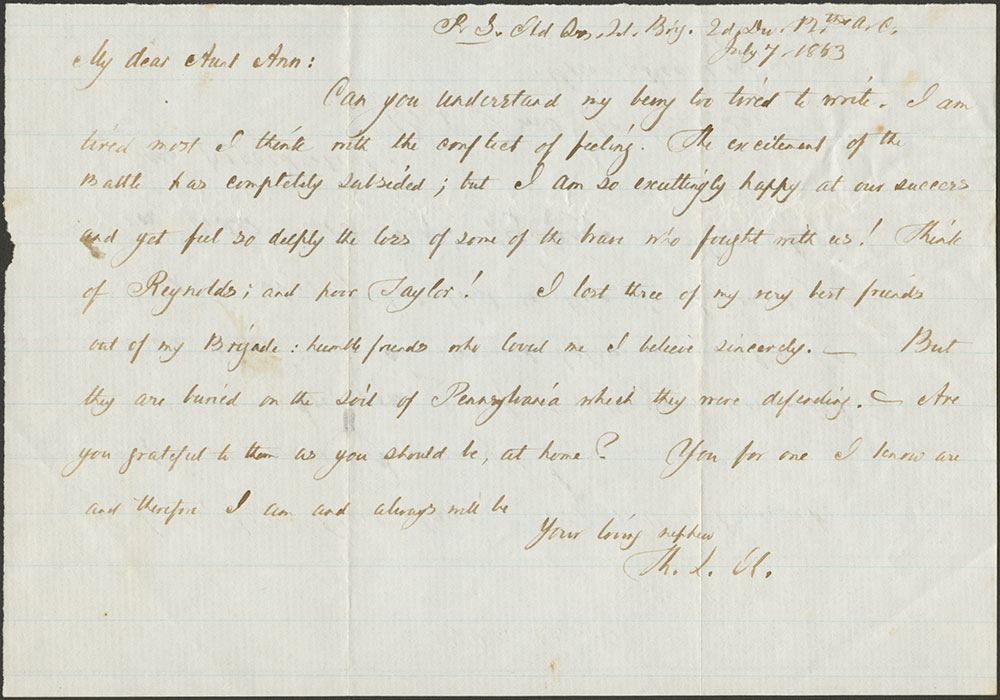

Thomas L. Kane to Aunt Ann. 7 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 22, Folder 2, Item 79)

I arrived before my Corps had fired a shot; but just in time to place my men in order and begin fighting. Does it not seem providential?

![Thomas L. Kane to Jane Duval Leiper [his mother]. 7 July, 1863](http://files.lib.byu.edu/exhibits/civilwar/families/kane_leiper_july_7_1863.jpg) View 1 image

View 1 image

Thomas L. Kane to Jane Duval Leiper [his mother]. 7 July, 1863 (Vault MSS 792, Box 22, Folder 2, Item 80)

I felt that you were praying for us yesterday and the day before; and I know you are thankful that we have conquered the invader. Did you not think once or twice of the great ambition of my heart, the house and home I am to build for you on top of the exceeding high mountain? I had to admit that I had to commence from the very beginning, but the hardest part of the work is done. Haven’t I saved you a country? The land and the lumber and the money will soon be saved up too ...

"Divine Retribution"

Don Carlos Salisbury was the son of Katharine Smith Salisbury, the younger sister of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Don Carlos was born in 1841 in a small village near Carthage, Illinois. As the main body of the Latter-day Saints left Nauvoo, Don Carlos remained in Illinois with his family.

At the age of nineteen, Don Carlos and his older brother Alvin volunteered to fight for the Union shortly after the outbreak of hostilities. While Alvin soon returned home due to illness, Don Carlos served in the 16th and 60th Regiments Illinois Volunteer Infantry for over three years, and saw combat in Missouri, Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia before being discharged in 1864.

He felt the particularly bitter fighting in Missouri was divine retribution for the expulsion of the Mormons and his family. Wounded in action, Don Carlos carried the scars of the Civil War with him throughout his life. He died on 6 April, 1919 at the age of 77.

View 3 images

View 3 images

Don Carlos Salisbury letter, 8 May, 1861

Don Carlos and Alvin Salisbury volunteered for the Illinois infantry in May of 1861. Shortly thereafter, an exuberant Don Carlos wrote home to describe his induction into the life of a soldier. Already, Don Carlos wrote, the health of the camp was a primary concern, and for good reason. Of the 170 casualties his regiment suffered during the war, two thirds were from disease, not combat.

Despite the specter of ill health, Don Carlos noted that the general feeling in the camp was one of excitement and adventure. They think we may have a little fun with Missouri, he reported. Sure enough, the regiment was soon transferred to Missouri, a contested border state. There, in a battle at a Confederate fort in Utica, Missouri, Don Carlos led the charge that forced the Confederates to abandon the fort and personally captured the enemy’s flag. The flag was displayed for many years in Springfield, Illinois. Meanwhile, Don Carlos was promoted to Corporal for his valor.

View 4 images

View 4 images

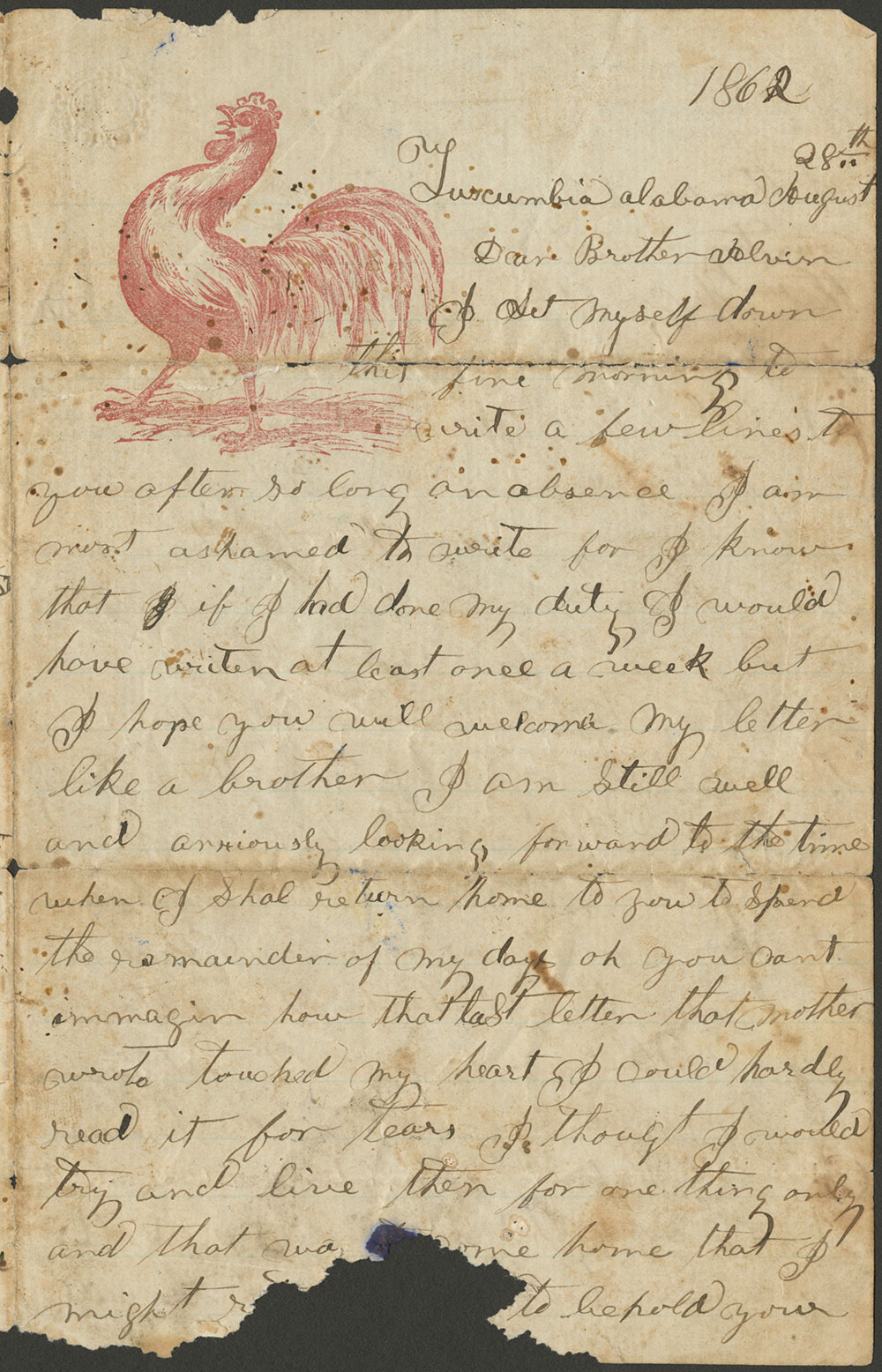

Don Carlos Salisbury letter to Alvin Salisbury, 28 August, 1862.

After nearly a year and an half in the infantry, the war looked very different to Don Carlos Salisbury. His brother Alvin had returned home due to poor health, many of his old friends were dying of disease or in combat, and he was beginning to miss his home and family.

As he struggled with the difficulties of war, Don Carlos relied on his increasing faith in Jesus Christ to give him strength to endure. I have set my heart on something higher than worldly affairs, he wrote to his brother, and in other letters he began to compare himself to Lamoni, a pacifist king from the Book of Mormon. As a believer in Christ, he felt he was able to be happy under all misfortunes and was able to bear separation from his loved ones because, as he observed, if they don’t meet again in this world they will meet in heaven. This one happy thought gave Don Carlos hope during the dark days of war.

View 2 images

View 2 images

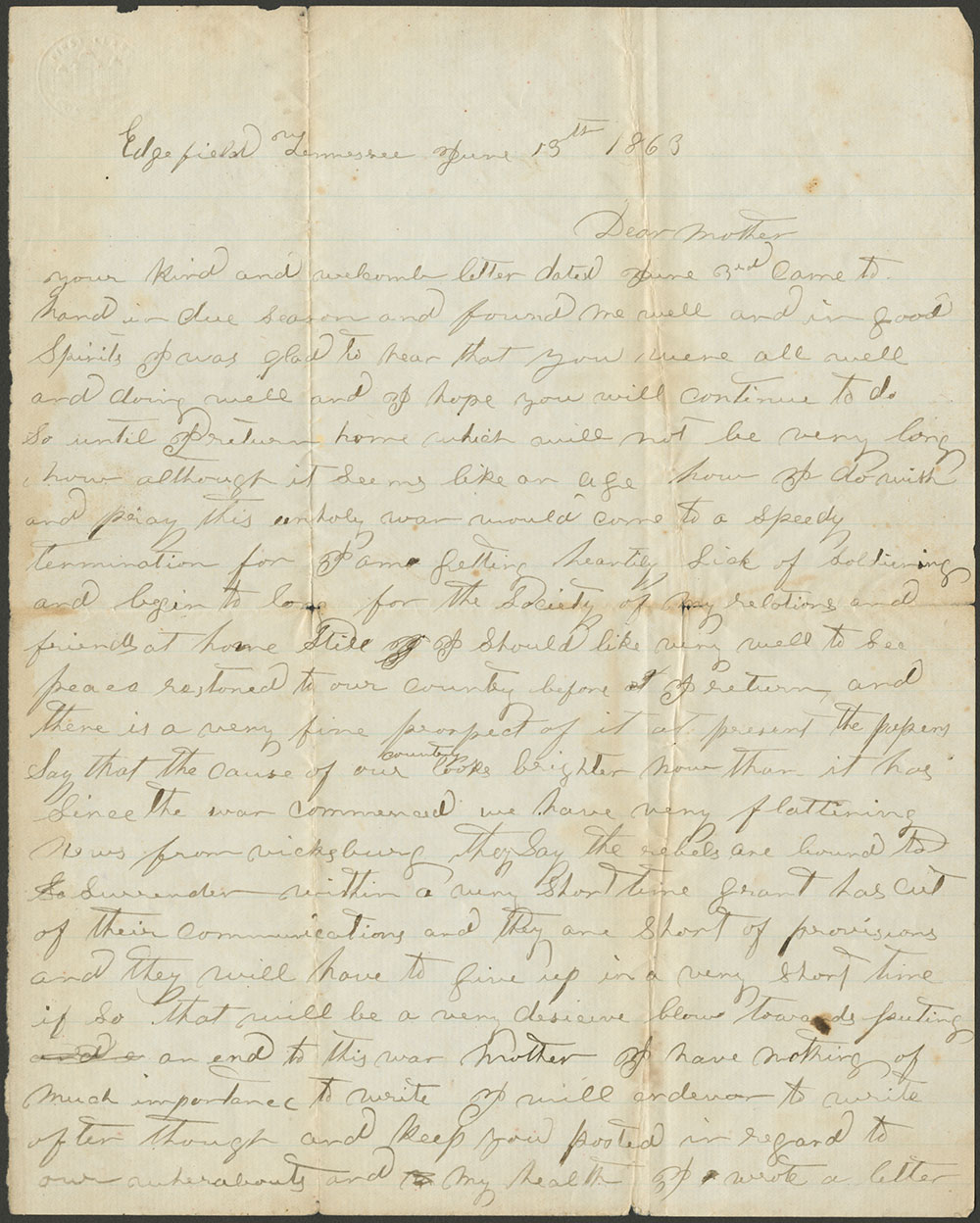

Don Carlos Salisbury to Katherine Smith Salisbury, 13 June, 1863

As the war dragged on, the enthusiasm of the young volunteer began to waver. Though he was still passionate about his cause, the hardships of war, the loss of many of his comrades and friends to battle or disease, and the drama of camp life took a heavy toll.

I should like very well to see peace restored to our country, he wrote in the summer of 1863. Yet, he was growing tired of this unholy war and longed for the society of my relations and friends at home. He candidly told his mother, I am getting heartily sick of soldiering.

It was another year before Don Carlos returned home, a changed and weary man.

Brother Fighting Against Brother

Gavin Drummond Hunt married Catherine Amelia Burgess in the early 1830s and had five children: George Washington Hunt, Mary D. Hunt, Philemon Burgess Hunt, Gavin Drummond Hunt Jr., and Albert G. Hunt. Shortly after their last child was born, Mrs. Hunt passed away.

With five children to look after, Mr. Hunt remarried Letitia Dudley. The family lived in Lexington, Kentucky, a border state during the war that did not secede, despite it being a slave state. This led to divisions in the state and even among family members, as was the case with the Hunt family.

Before the War commenced, Mary had moved to New Jersey and married Dr. Lewis Craig. Her father and brothers sent her numerous letters during the Civil War chronicling the social and political climate during the war, major battles, and the impact of the war on her family.

View 3 images

View 3 images

Philemon Burgess Hunt to Mary D. Craig 24 May, 1862 (MSS 7809)

Just as the nation was divided by the war, so was the Hunt family. Two sons, George and “Allie” (Albert) Hunt, enlisted in a Confederate cavalry regiment; meanwhile, Philemon Burgess and Gavin Drummond Hunt Jr. followed suit by joining the Union army. Although the brothers were divided by conflicting loyalties, they had no desire to take up arms against each other. Philemon Burgess was glad to know [George] [was] in Cavalry instead of Infantry as there [was] much less danger in the former corps. And again there [was] not much probability of he and I coming in contact.

Unfortunately, Philemon Burgess’ wish was not realized, as brother literally took up arms against brother. Philemon Burgess was shot in the knee in the Battle of Chicamauga in 1863 and never returned to battle. His brothers continued fighting and in November 1863, as part of the Union victory at the Battle of Missionary Ridge, Gavin Drummond was killed. Their brother George, fighting for the Confederacy, was present at both battles under General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler’s command. This war pitted one side of the family against the other with bloody consequences.

View 6 images

View 6 images

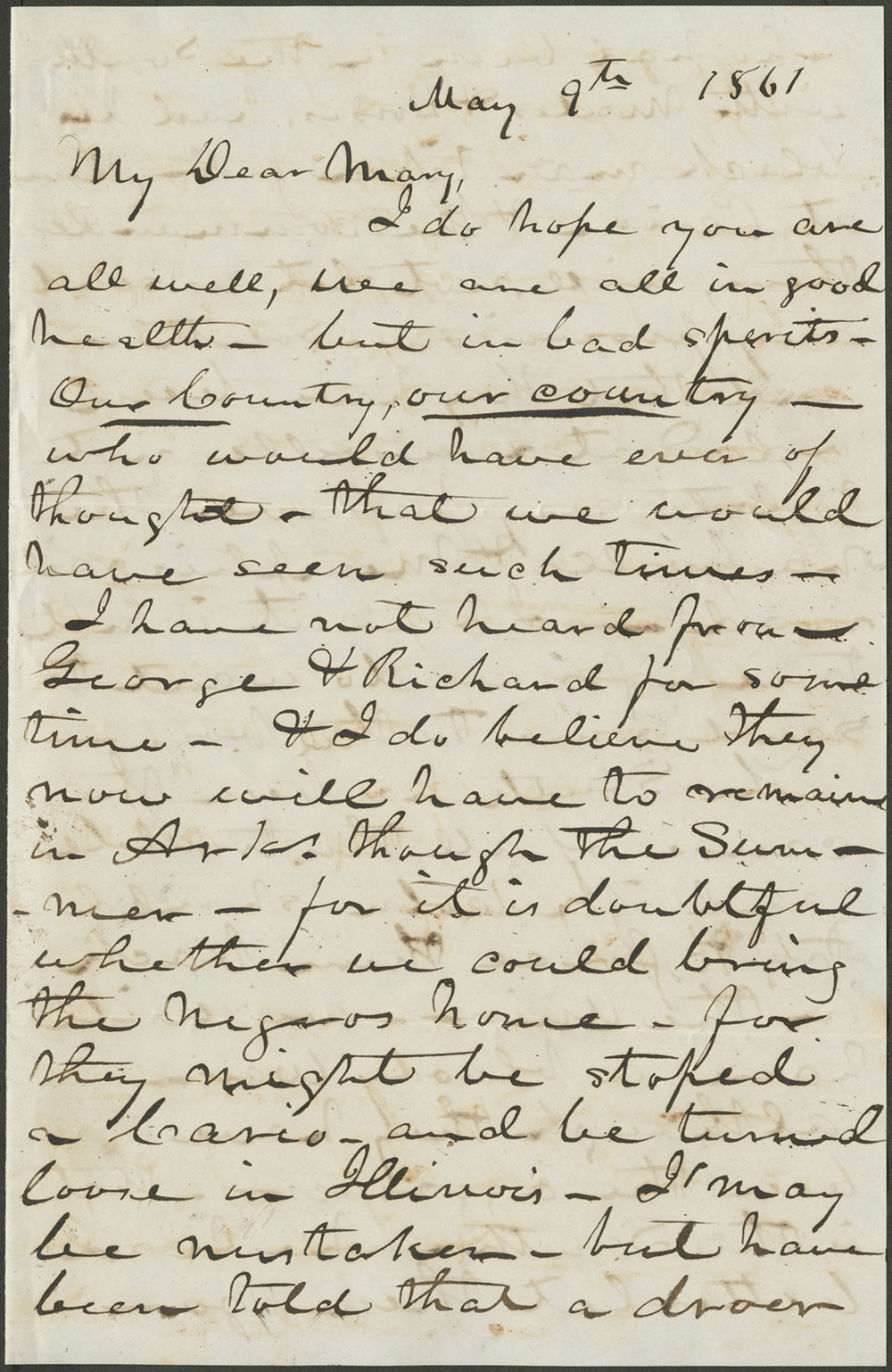

Drummond Hunt to Mary D. Craig 9 May, 1861 (MSS 7809)

In a May 1861 letter to his daughter Mary, written just one month following the outbreak of war, Gavin Drummond Hunt expressed his own grave concerns for the future of his country. Lamenting the terrible divisions between North and South, Hunt exclaimed: Our Country, our country — who would have ever of thought — that we would have seen such times.

Later on in that same letter he professed his allegiance to the Union, decried the actions of the South, and blamed them for bringing on this war — Unholy War.

Though he was staunchly for the Union, not all of his family agreed with him.